The Maya City-States

Mayan civilization reached its height between 250 and 900 C.E. Mayans stretched over the southern part of Mexico and much of what is now Belize, Honduras, and Guatemala. Most lived in or near one of the approximately 40 cities that ranged in size from 5,000 to 50,000 people. At its peak, as many as 2 million Mayans populated the region.

Mayan Government The main form of Mayan government was the city-state, each ruled by a king and consisting of a city and its surrounding territory. Most rulers were men. However, when no male heir was available or old enough to govern, Mayan women ruled. Wars between city-states were common. At times, city-states were overthrown. However, Mayans rarely fought to control territory. More often they fought to gain tribute—payments from the conquered to the conqueror—and captives to be used as human sacrifices during religious ceremonies.

Each Mayan king claimed to be descended from a god. The Mayans believed that when the king died, he would become one with his ancestor- god. The king directed the activities of the elite scribes and priests who administered the affairs of the state. Royal rule usually passed from father to son, but kings who lost the support of the people were sometimes overthrown. The common people were required to pay taxes, usually in the form of crops, and to provide labor to the government. City-states had no standing armies, so when war erupted, governments required citizens to provide military service. No central government ruled all Mayan lands, although often one city-state was the strongest in a region and would dominate its neighbors.

Mayan Religion, Science, and Technology The Mayans were innovative thinkers and inventors. For example, they incorporated the concept of zero into their number system, developed a complex writing system, and learned to make rubber out of liquid collected from rubber plants.

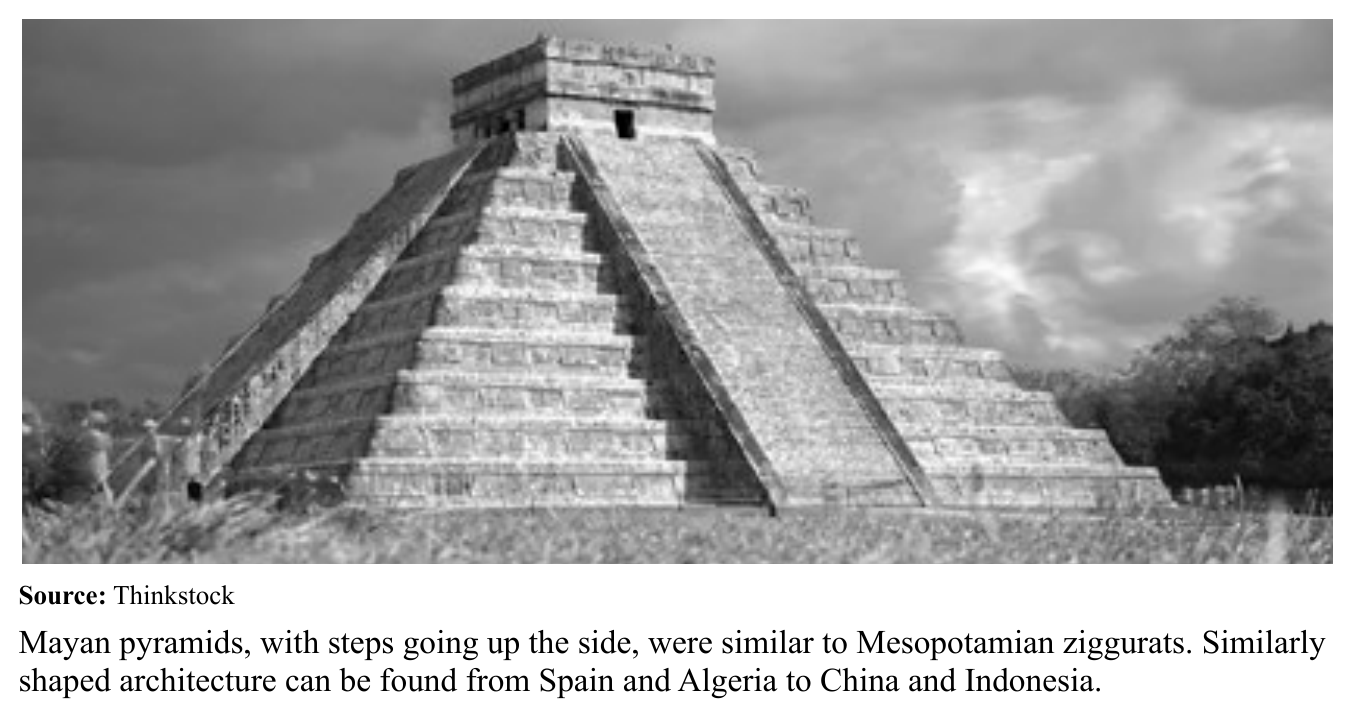

Mayan science and religion were linked through astronomy. Based on the calendar, priests decided when to celebrate religious ceremonies and whether to go to war. As a result, keeping an accurate calendar was very important. Although the Mayans had no telescopes, they made very precise observatories atop pyramids such as the one at Chichen Itza. Their observations enabled priests to design a calendar more accurate than any used in Europe at the time.

One task of priests, who could be either male or female, was to conduct ceremonies honoring many deities. Among the most important deities were those of the sun, rain, and corn. Mayans made offerings to the gods so prayers might be answered. War captives were sometimes killed as offerings. (Connect: Compare the political structures of the Mayans with the political structures of South Asia. See Topic 1.3.)