Centralizing Control in Europe

England’s King James I believed in the divine right of kings, a common claim from the Middle Ages that the right to rule was given to a king by God. Under this belief, a king was a political and religious authority. As seen in the quote above, James believed himself outside of the law and any earthly authority and saw any challenge toward him as a challenge to God.

England’s Gentry Officials In England, the Tudors (ruled 1485–1603) relied on justices of the peace, officials selected by the landed gentry to “swear that as Justices of the Peace . . . in all articles in the King’s Commission to you directed, ye shall do equal right to the poor and to the rich after your cunning wit, and power, and after the laws and customs of the realm and statutes thereof made,” according to their oath of office. In other words, their job was to maintain peace in the counties of England, even settling some legal matters, and to carry out the monarch’s laws. The number and responsibilities of the justices of the peace increased through the years of Tudor rule, and they became among the most important and powerful groups in the kingdom. Under Tudor rule, the power of feudal lords weakened. Many seats in the House of Commons in Parliament were occupied by justices of the peace. The justices of the peace as well as the Parliament, which had been established in 1265, gave legitimacy to the monarch’s claim to authority.

Parliament also checked the monarch’s powers. In 1689, England’s rulers William and Mary signed the English Bill of Rights, which assured individual civil liberties. For example, legal process was required before someone could be arrested and detained. The Bill of Rights also guaranteed protection against tyranny of the monarchy by requiring the agreement of Parliament on matters of taxation and raising an army.

Absolutism in France In contrast to developments in England, the French government became more absolute—directed by one source of power, the king, with complete authority—in the 17th and 18th centuries. Henry IV (ruled 1589–1610) of the House of Valois listened to his advisor Jean Bodin, who advocated the divine right of the monarchy. Building on these ideas, Louis XIII (ruled 1610–1643) and his minister Cardinal Richelieu moved to even greater centralization of the government and development of the system of intendants. These intendants were royal officials —bureaucratic elites— sent out to the provinces to execute the orders of the central government. The intendants themselves were sometimes called tax farmers because they oversaw the collection of various taxes in support of the royal governments.

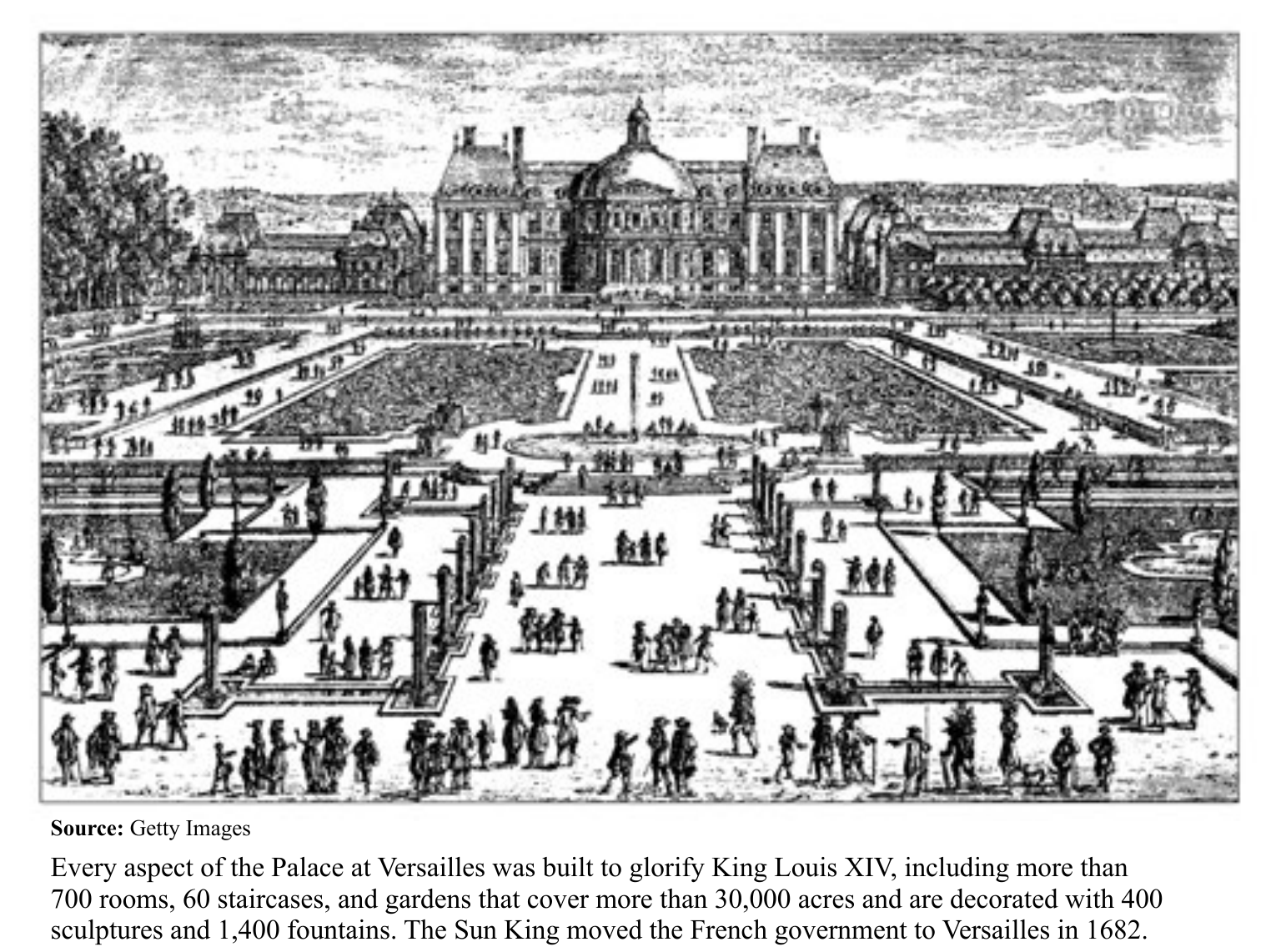

The Sun King, Louis XIV (ruled 1643–1715), espoused a theory of divine right and was a virtual dictator. His aims were twofold, just as those of Richelieu had been: He wanted to hold absolute power and expand French borders. Louis declared that he was the state: “L’etat, c’est moi.” He combined the lawmaking and the justice system in his own person—he was absolute. He kept nobles close to him in his palace at Versailles, making it difficult for them to act independently or plot against him. Louis and his successors’ refusal to share power eventually weakened the French government.