An Era of Rights

In December of 1948, the United Nations laid the groundwork for an era of rights when it adopted a foundational document, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, asserting basic rights and fundamental freedoms for all human beings. It stated that everyone is entitled to these rights without distinctions based on “race, colour [color], sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.”

The UN and Human Rights Since its creation, the United Nations has promoted human rights, basic protections that are common to all people. As part of its humanitarian work, the UN created the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) in 1946 to provide food for children in Europe who were still suffering more than a year after the end of World War II. In 1948, the UN formalized its position on human rights in the Universal Declaration. Since that time, the UN has investigated abuses of human rights, such as genocide, war crimes, government oppression, and crimes against women.

The International Court of Justice is a judicial body set up by the original UN charter. It settles disputes over international law that countries bring to it. Also called the World Court, it has 15 judges, and each must be a citizen of a different country. It often deals with border disputes and treaty violations.

Another main aim of the UN is to protect refugees, people who have fled their home countries. In times of war, famine, and natural disasters, people often leave their country and seek refuge in a safe location. Working through sub-agencies such as NGOs (non-governmental organizations) and the agency UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees), the UN provides food, medicine, and temporary shelter. Among the earliest refugees the UN helped were Palestinians who fled the disorder when the UN partitioned Palestine to create the state of Israel in 1948.

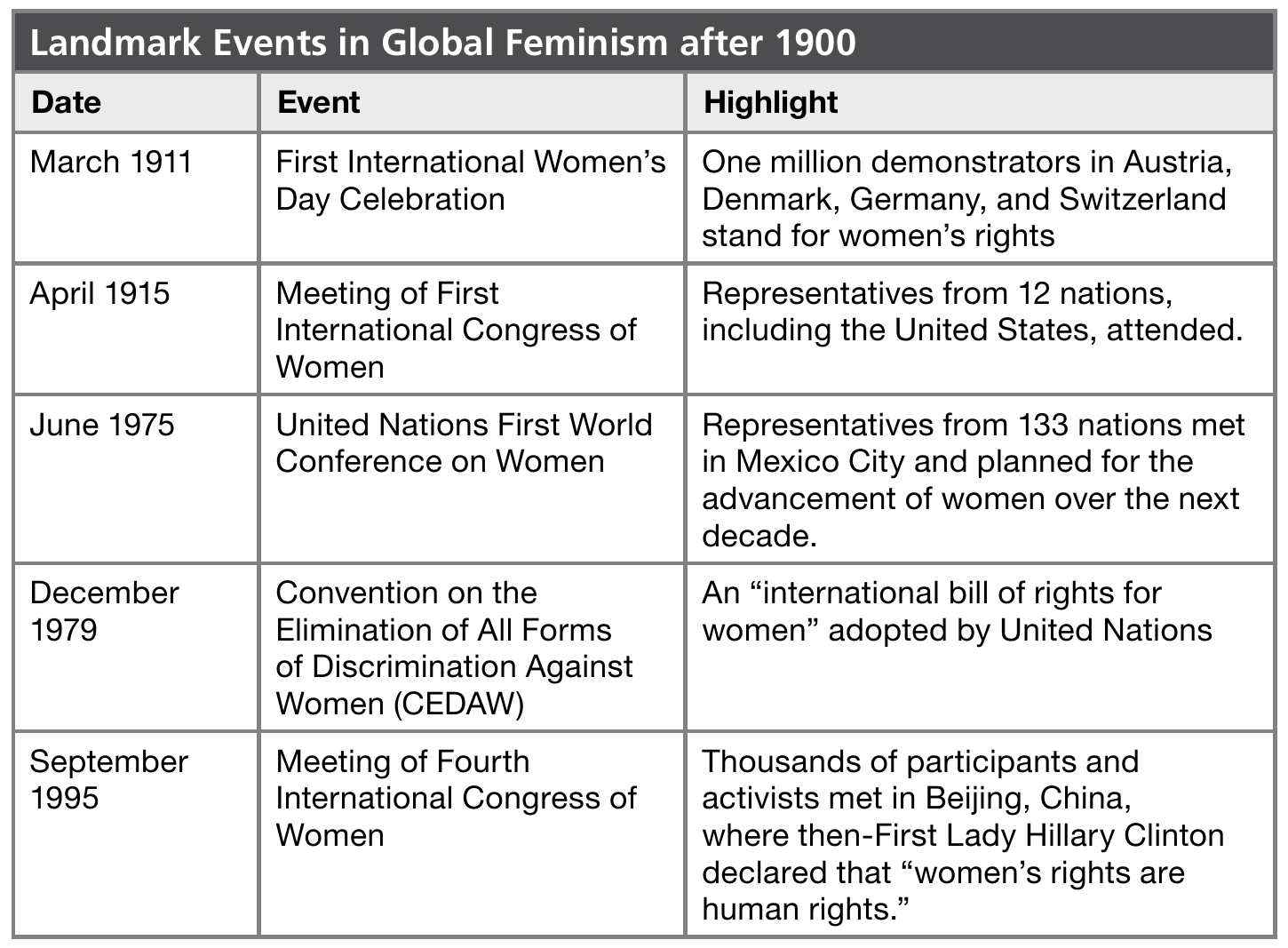

Global Feminism On January 21, 2017, the day after Donald Trump’s inauguration as president, the Women’s March on Washington drew about 500,000 demonstrators standing up for women’s rights and other concerns. However, the march drew even more power from the millions more demonstrators who took part in locations on every continent around the globe, from Antarctica to Zagreb, Croatia and from Buenos Aires, Argentina to Mumbai, India. As many as five million people stood together that day representing a global solidarity for women’s rights. That march was the most dramatic sign of global feminism, but other landmark events since 1900 had done their part to solidify the movement.

The 1979 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women outlined many rights and protections that are cornerstones of global feminism:

• The right to vote and to hold office

• The right to freely choose a spouse

• The right to access the same education as men

• The right to access family planning resources and birth control.

Cultural and Religious Movements Discourse on rights also became part of cultural and religious movements. For example, the Negritude Movement, which took root primarily in French West Africa, emphasized pride in “blackness,” the rejection of French colonial authority, and the right to self-determination. Léopold Sédar Senghor of Senegal wrote poems about the beauty and uniqueness of African culture and is now regarded as one of the 20th century’s most distinguished French writers. (Senghor later served as first president of independent Senegal.) During the 1920s and 1930s, American intellectuals such as W. E. B. Du Bois, Richard Wright, and Langston Hughes wrote movingly about the multiple meanings of “blackness” in the world. What many now refer to as “black pride”of the 1960s had its roots in the Negritude Movement

Inherent rights became a focus of a religious ideology as well. Liberation theology, which combined socialism with Catholicism, spread through Latin America in the 1950s and 1960s. It interpreted the teachings of Jesus to include freeing people from the abuses of economic, political, and social conditions. Part of this liberation included redistributing some wealth from the rich to the poor. In many countries, military dictators persecuted and killed religious workers who embraced liberation theology.

However, advocates of liberation theology had a few notable successes. In Nicaragua, they helped a rebel movement topple a dictator and institute a socialist government. In Venezuela, President Hugo Chávez was deeply influenced by the movement. Then, in 2013, the Roman Catholic Church selected a cardinal from Argentina as pope, the first one from Latin America. The new leader, who took the name Pope Francis, reversed the Vatican’s opposition to liberation theology.