The Great Depression

From today’s perspective, the effects of World War I can look small compared to the even greater destruction caused by World War II. However, the effects were massive. Many Western Europeans felt bewildered. World War I brought anxiety to the people who suffered through it. The Allied nations, though victorious, had lost millions of citizens, both soldiers and civilians, and had spent tremendous amounts of money on the international conflict. The defeated Central Powers, particularly Germany and the countries that emerged from the breakup of Austria-Hungary, suffered even greater losses.

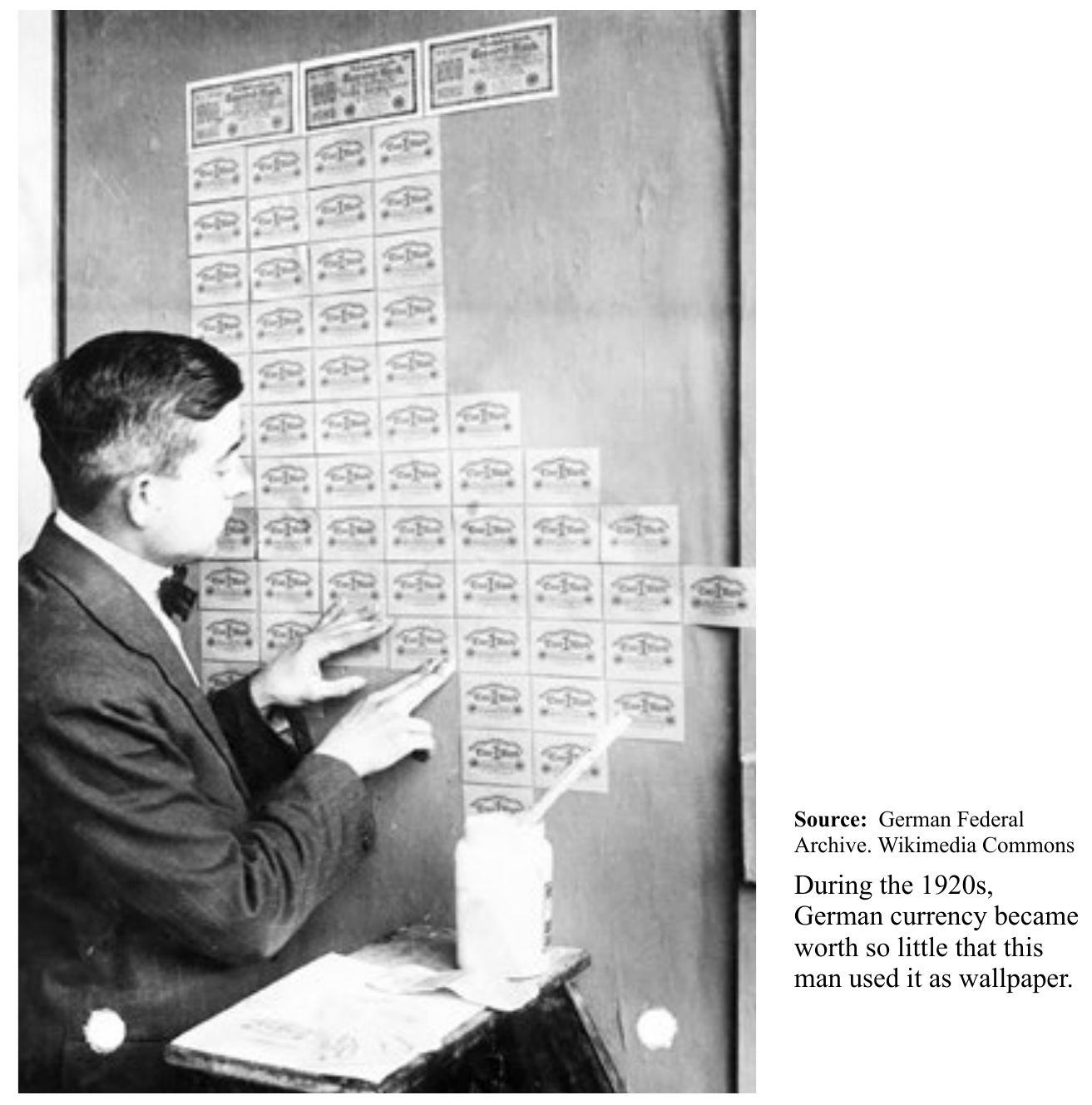

The Treaty of Versailles forced Germany to pay billions of dollars in reparations to the war’s victors. War-ravaged Germany could not make these payments, so its government printed more paper money in the 1920s.

This action caused inflation, a general rise in prices. Inflation meant that the value of German money decreased drastically. To add to the sluggish postwar economy, France and Britain had difficulty repaying wartime loans from the United States, partly because Germany was having trouble paying reparations to them. In addition, the Soviet government refused to pay Russia’s prerevolutionary debts.

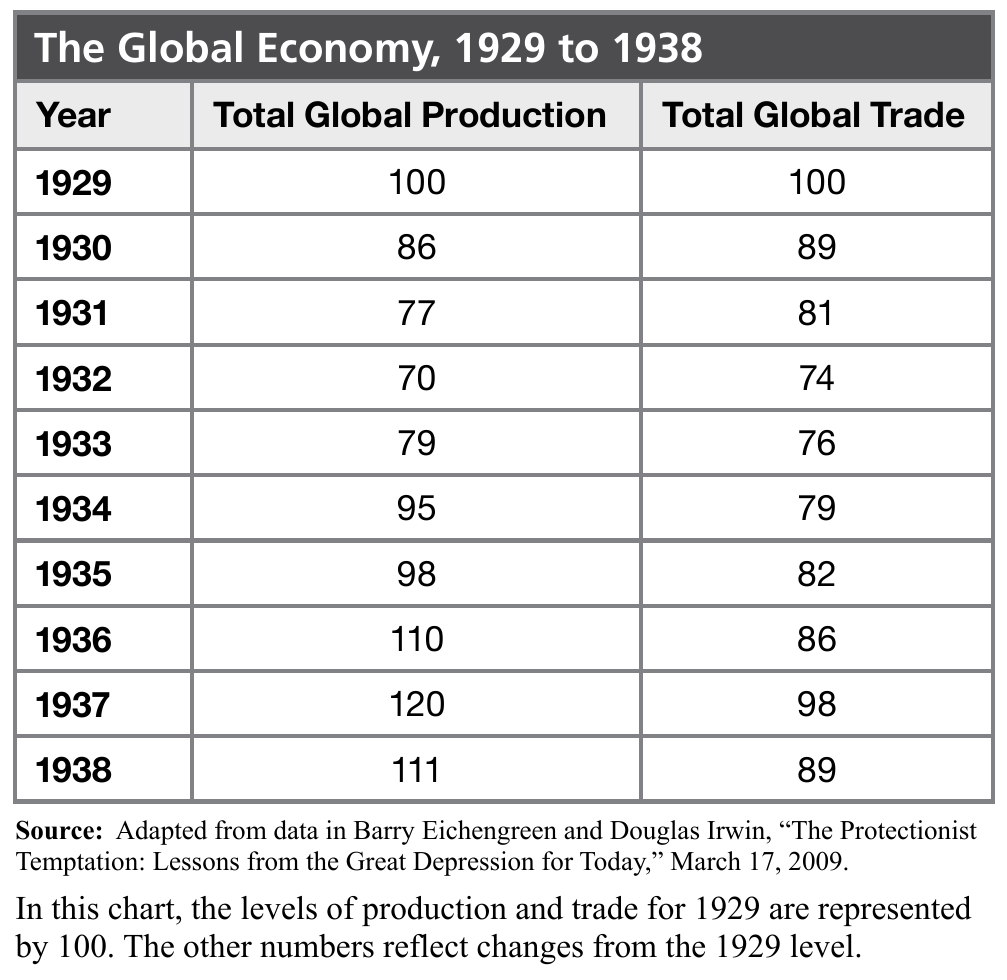

Global Downturn Although the 1920s brought modest economic gains for most of Europe, the subsequent Great Depression ended the tentative stability. Agricultural overproduction and the United States’ stock market crash in 1929 were two major causes of the global economic downturn. American investors who had been putting money into German banks removed it when the American stock market crashed. In addition to its skyrocketing inflation, Germany then had to grapple with bank failures. Germany thus suffered more than any other Western nation during the Great Depression. The economies of Africa, Asia, and Latin America suffered because they depended on the imperial nations that were experiencing this enormous economic downturn. Japan also suffered during the Depression because its economy depended on foreign trade. With the economic decline in the rest of the world, Japan’s exports were cut in half between 1929 and 1931.

Keynesian Economics The Great Depression inspired new insights into economics. British economist John Maynard Keynes rejected the laissez- faire ideal. He concluded that intentional government action could improve the economy. During a depression, he said, governments should use deficit spending (spending more than the government takes in) to stimulate economic activity. By cutting taxes and increasing spending, governments would spur economic growth. People would return to work, and the depression would end.

New Deal The administration of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt used Keynes’s ideas to address the Great Depression in the United States. Roosevelt and his backers created a group of policies and programs known collectively as the New Deal. Its goal was to bring the country relief, recovery, and reform: relief for citizens who were suffering, including the poor, the unemployed, farmers, minorities, and women; recovery to bring the nation out of the Depression, in part through government spending; and reform to change government policies in the hopes of avoiding such disasters in the future.

By 1937, unemployment was declining and production was rising. Keynesian economics seemed to be working. However, Roosevelt feared that government deficits were growing too large, so he reversed course. Unemployment began to grow again. The Great Depression finally ended after the United States entered World War II in 1941 and ran up deficits for military spending that dwarfed those of the New Deal programs.

Impact on Trade The Great Depression was a global event. Though it started in the industrialized countries of the United States and Europe, it spread to Latin America, Africa, and Asia. By 1932, more than 30 million people worldwide were out of work. People everywhere turned to their governments for help. As unemployment increased, international trade declined, a decline made worse as nations then imposed strict tariffs, or taxes on imports, in an effort to protect the domestic jobs they still had.

In contrast to most countries, Japan dug itself out of the Depression relatively rapidly. Japan devalued its currency; that is, the government lowered the value of its money in relation to foreign currencies. Thus, Japanese-made products became less expensive than imports. Japan’s overseas expansionism also increased Japan’s need for military goods and stimulated the economy.