Similarities Among Networks of Exchange

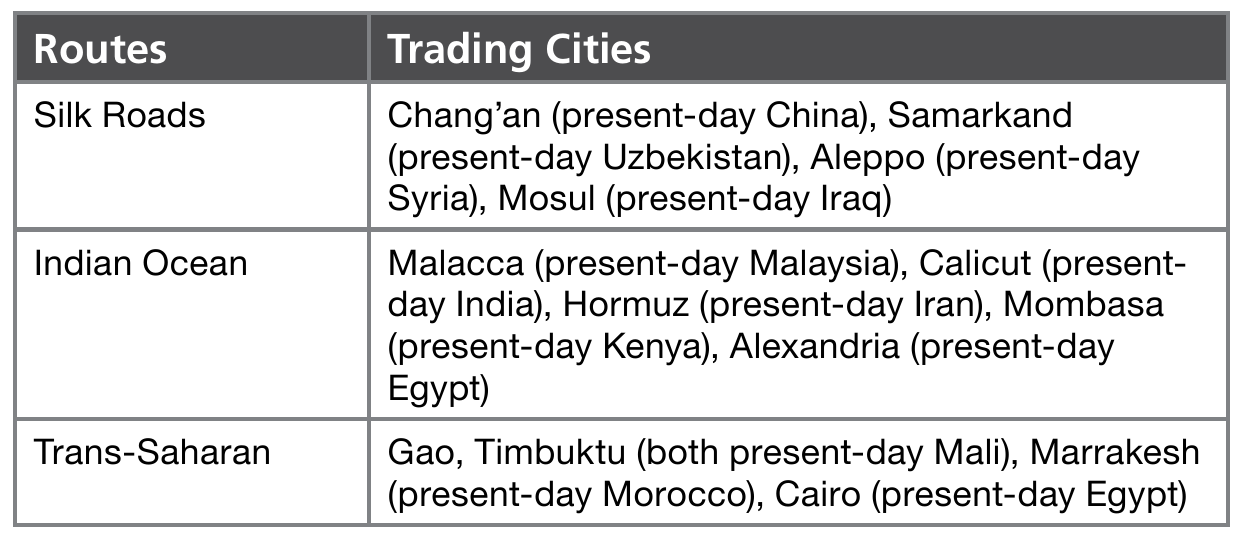

Several major trading networks connected people in Africa, Europe, and Asia in the years between c. 1200 and c. 1450:

• the Silk Roads through the Gobi Desert and mountain passes in China and Central Asia to Southwest Asia and Europe, on which merchants tended to specialize in luxury goods

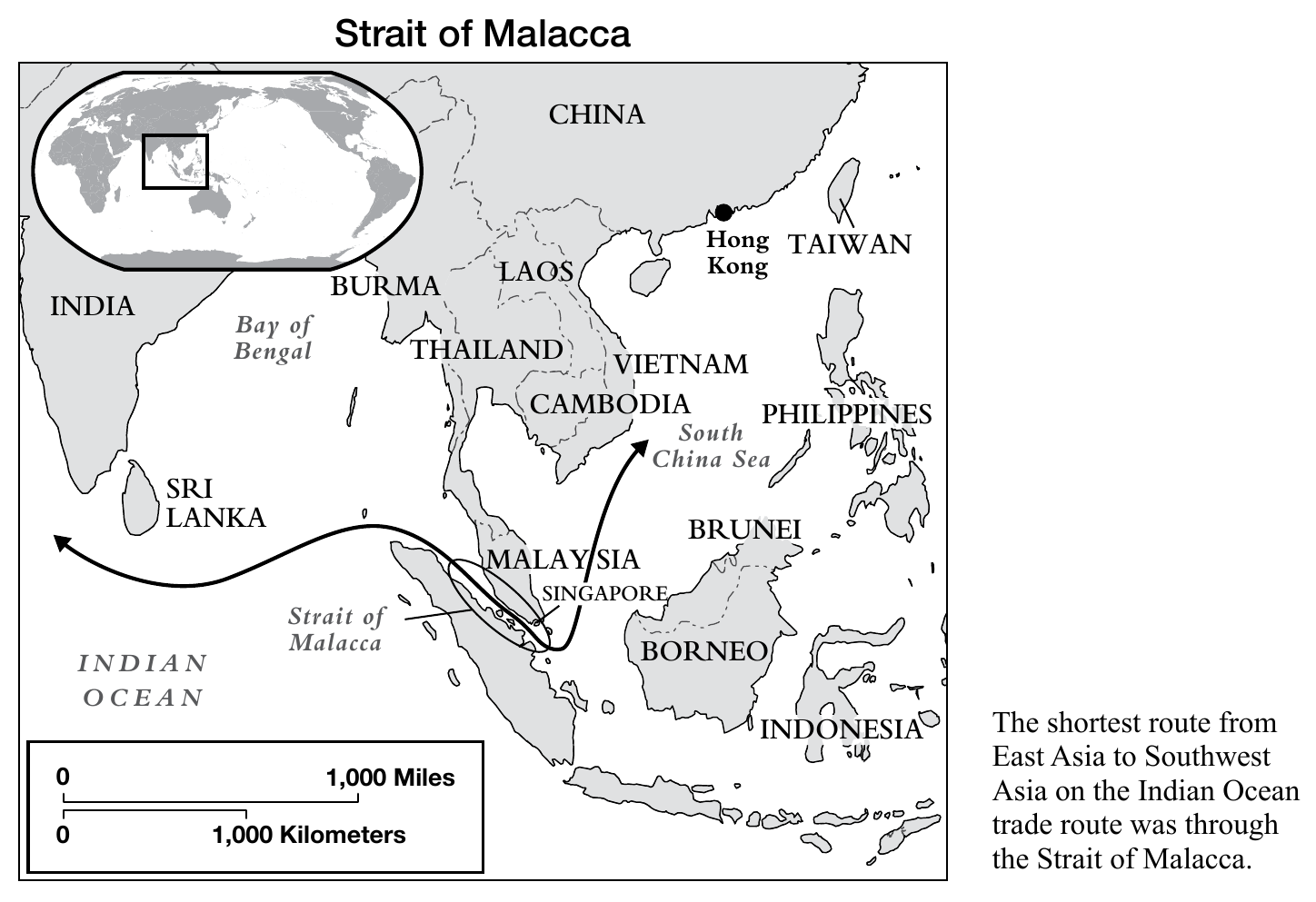

• the monsoon-dependent trade routes in the Indian Ocean linking East Asia with Southeast Asia, South Asia, and Southwest Asia, on which merchants exchanged goods too heavy to transport by land

• the trans-Saharan trade routes from North Africa and the Mediterranean Basin across the desert to West and East Africa, on which merchants traded salt from North Africa with gold from the kingdoms south of the desert While each exchange network had its unique characteristics, all were similar in their origins, purpose, and effects.

Origins Interregional trade began well before the common era as agrarian cultures consolidated into stable settlements. The trade that flourished between c. 1200 and c. 1450 built on the routes these early traders—and conquerors— first traced. As kingdoms and empires expanded, so did the trade routes they controlled and traveled.

The Postclassical trading networks also needed the stability of established states to grow and expand. Stable kingdoms, caliphates, city-states, or empires assured merchants that the routes and the merchants themselves would be protected—which is why the wealthy merchants in Calicut could walk away from their cargoes knowing they would not be stolen. Stable polities also supported the technological upgrades that made trade more profitable— nautical equipment such as the magnetic compass and lateen sail, high-yielding strains of crops, and saddles to allow for the carriage of heavy loads of goods.

Purpose The trading networks shared an overall economic purpose: to exchange what people were able to grow or produce for what they wanted, needed, or could use to trade for other items. In other words, their purpose was primarily economic. However, as you have read, people exchanged much more than just products. Diplomats and missionaries also traveled the trade routes, negotiating alliances and proselytizing for converts. Together, merchants, diplomats, and missionaries exchanged ways of life as well as economic goods.

Effects All the exchange networks also experienced similar effects. Because of the very nature of a network—which can be described as a fabric of cords crossing at regular distances, knotted for strength at the crossings— the trade routes all gave rise to trading cities, the “knots” that held the network together.

The growth of trading cities gave rise to another effect of the trade networks: centralization. Malacca, for example, grew wealthy from the fees levied on ships and cargoes passing through the Strait of Malacca. To prevent piracy, Malacca used its wealth in part to develop a strong navy—an endeavor that required centralized planning. Trading cities along each of the trade routes underwent similar developments, using their wealth to keep the routes and the cities safe.

Another aspect of trade in the cities that encouraged centralization was the desire for a standardized currency. Widely accepted currencies sped up transactions and enabled merchants to measure the value of products.