Effects of Migration on Receiving Societies

Immigrants were interested in a new economic start but intent on carrying with them their own traditions and culture. Ethnic enclaves, clusters or neighborhoods of people from the same foreign country, formed in many major cities of the world. In these areas inhabitants spoke the language of their home country, ate the foods they were familiar with from home, and pursued a way of life similar to that they had known in their home countries. At the same time, they influenced the culture of their new homes which absorbed some of the migrants’ cultural traditions.

Chinese Enclaves

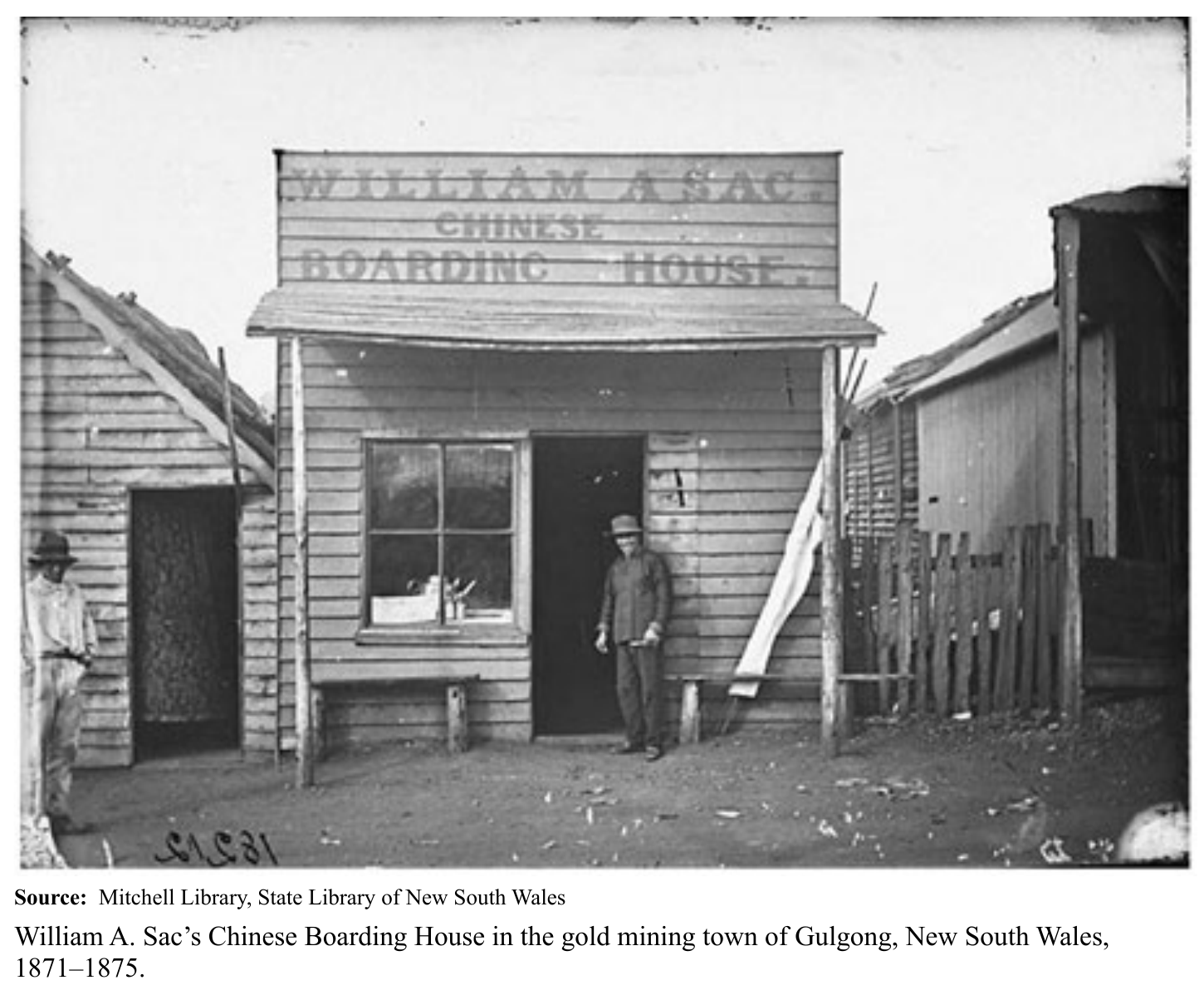

Many Chinese emigrated in search of work during the latter half of the 19th century—some to work on sugar plantations or for other agricultural endeavors, others to work in industry and transportation. Together, they spread Chinese culture around the world.

Southeast Asia The Chinese who migrated to Southeast Asia thrived under colonial rule. In Indochina, the French encouraged them to engage in commerce. In Malaya, they managed opium farms and controlled opium distribution for the British. In the Dutch East Indies, some Chinese held posts with the colonial government. As time went on, many Chinese throughout the region became business owners and traders, often founding family businesses. Some Chinese acquired great wealth as moneylenders or through international trade. By the end of the 19th century, the Chinese controlled trade throughout Southeast Asia and were a significant presence in the region.

The Americas Chinese immigrants first came to the United States in large numbers during the height of the California gold rush. Many worked in mines, but others found work on farms or in San Francisco’s garment industry. Chinese laborers became indispensable during the construction of the first transcontinental railroad.

Between 1847 and 1874, some 225,000 Chinese laborers were sent to Cuba and Peru on eight-year contracts. Almost all of them were male, and 80 percent of them were sent to work on sugar plantations alongside enslaved Africans in Cuba and replacing enlaved workers in Peru, where slavery had been abolished. Other Chinese in Cuba were employed as servants, in cigarette factories, and in public works projects. Several thousand contract laborers in Peru helped build the Andean railroad and worked in the guano mines. In the 1870s, some Chinese built settlements in the Peruvian Amazon, where they were active as merchants and grew rice, beans, sugar, and other crops.

In each area they lived, Chinese immigrants left their cultural stamp. Some Peruvian cuisine is a fusion of Chinese foods and ingredients and cooking styles of Peru. As in other areas, Chinese immigrants sometimes married local people and thus contributed to the multicultural diversity of populations.

Indian Enclaves

The British Empire abolished slavery in 1833. However, it was replaced with a system that was little better, indentured servitude. Indians were among the first indentured servants sent to work in British colonies.

Indians in Africa Many Indians went to Mauritius, islands off the southeast coast of Africa, and Natal, a colony that is today part of South Africa, as indentured servants on sugar plantations. In Natal and British East Africa, they built railways. Nearly 32,000 indentured Indian workers went to Kenya to work on railroad construction between 1886 and 1901, but only about 7,000 chose to stay. Today, Indians continue to make up significant parts of the population of these regions.

Both Hindus and Muslims emigrated from India to South Africa. The Hindus brought with them their caste system and the social laws that stem from it, but they soon abandoned the caste system. In contrast, many kept up Hindu traditions and had alters in their homes to honor deities.

The Hindu and Muslim Indian population of South Africa was divided by class, language, and religion. However, Indians in South Africa shared the injustice of discrimination, which became central to the work of a young Indian named Mohandas Gandhi. He arrived in Pretoria, South Africa, in 1893, where he intended to practice law. After suffering repeatedly from racial discrimination, Gandhi became an activist. He founded the Natal Indian Congress and worked to expose to the world the rampant discrimination against Indians in South Africa. In 1914 Gandhi returned to India, where he became a leader in the Indian nationalist movement against British rule.

Indians in Southeast Asia Between 1834 and 1937 India was the major source of labor for the British Southeast Asian colonies of Ceylon, Burma, and Malaya. Many Indians went to Malaya as indentured laborers. Indentured servitude was eventually replaced by the kangani system, under which entire families were recruited to work on tea, coffee, and rubber plantations in Ceylon, Burma, and Malaya. Their lives were less restricted than those of indentured laborers, and they had the advantage of having their families with them. It is estimated that about 6 million Indians migrated to Southeast Asia before the kangani system was abolished. Because Southeast Asia was relatively close, Indian workers there often kept close ties with India.

Indian traders settled in many countries where there were indentured laborers. They also looked for business opportunities throughout the British Empire, such as British East Africa.

Indians in the Caribbean Region So many Indians were sent to work on the sugar plantations in and around the Caribbean that today they comprise the largest ethnic group in Guyana and Trinidad and Tobago, and the second largest group in Suriname, Jamaica, Grenada, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Saint Lucia, Martinique and Guadeloupe. In many of the other Caribbean nations Indians constitute a sizable proportion of the population. In addition, they have blended ethnically with migrants from other parts of the world, creating a unique culture, affecting national cuisines, film, and music. Many of the countries in the region celebrate the arrival of the Indians with annual holidays or festivals.

Irish Enclaves in North America

Before the American Revolution, most Irish who came to North America were Protestant descendants of Scots who had previously migrated to Ireland. They are often referred to as Scots-Irish. Most came as indentured servants. Those who paid their own passage often went west to the frontier.

After the American Revolution, most new Irish immigrants who came to the United States settled in northern cities. Many others went to British North America (Canada), where they were able to get cheap land grants. By the 1830s, most new Irish immigrants were poorer than earlier settlers, and Catholic. Most of those who settled in cities worked in factories. Many of the men who came to the United States helped construct the canal system. In Canada as well as the United States, many Irish farmed. Most Irish immigrants were able to create decent lives for themselves and their children.

Half of the 3 million Irish who fled Ireland during the Great Famine came to North America. Most of this huge wave of Irish immigrants faced many hardships, not the least of them anti-immigrant nativist and anti- Catholic sentiments in the United States. Nevertheless, immigration from Ireland continued strong after the Great Famine ended until the 1880s, when it gradually slowed. Many of these new immigrants were single women who came to the United States looking for work and husbands. More than half became domestic servants. Many of the men who came during this period were unskilled laborers.

Wherever they settled, the Irish in the United States spread their culture— their lively dance music and holiday traditions such as the celebration of St. Patrick’s Day. They also had a strong influence on the conditions of laborers through their efforts at promoting labor unions, and their great numbers ensured the spread of Catholicism in the United States.

Second-generation Irish were often either white-collar or skilled blue- collar workers. Many became “stars” of the new popular culture that was taking root at the end of the century as boxers, baseball players, and vaudeville performers. Many second-and third-generation Irish, such as the Fitzgeralds and the Kennedys, became very wealthy and powerful.

Italians in Argentina

During the 18th and 19th centuries only the United States surpassed Argentina in the number of immigrants it attracted. The 1853 Argentine Constitution not only encouraged European immigration, but it also guaranteed to foreigners the same civil rights enjoyed by Argentine citizens.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Italians made up almost half of the European immigrants to Argentina. Today people of Italian descent make up more than 55 percent of the Argentine population. As a result, Italians have had an enormous influence on all aspects of Argentine culture and language. Argentine Spanish has absorbed many Italian words, and Italian is still widely spoken in Buenos Aires.

Argentina was underpopulated and had an enormous amount of fertile land, which appealed to Italian immigrants. Most of them were farmers, artisans, and day laborers. Wages in Argentina were much higher than in Italy. Agricultural workers, for example, could earn five to ten times as much in Argentina as in Italy. In addition, the cost of living, even in Buenos Aires, was much lower than that of many rural Italian provinces. Both of these factors allowed most immigrants to raise their standard of living greatly in a very short time. By 1909, Italian immigrants owned nearly 40 percent of Buenos Aires’ commercial establishments.