Rise of Right-Wing Governments

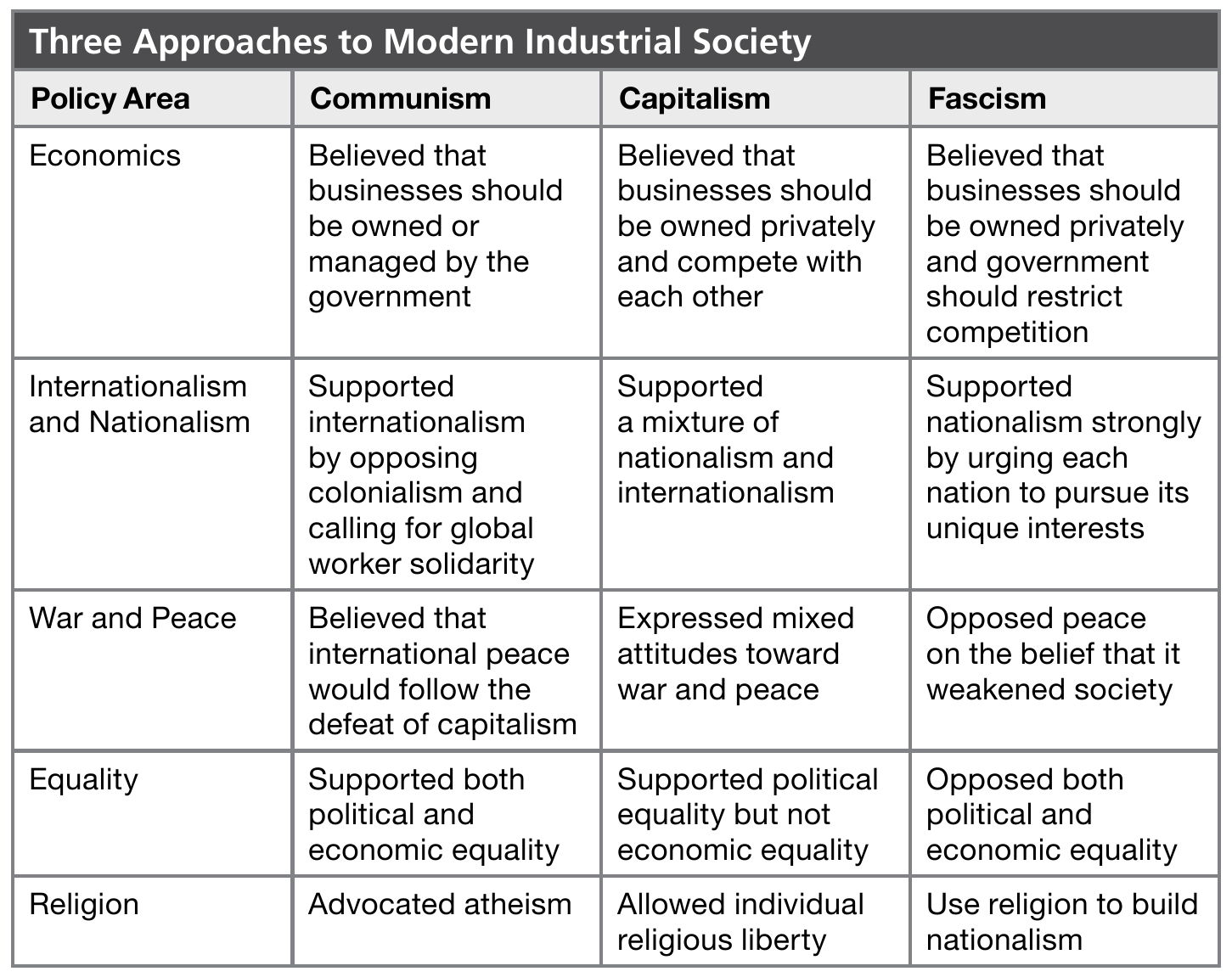

In some countries, the turn to the right was radical. A new political system known as fascism arose that appealed to extreme nationalism, glorified the military and armed struggle, and blamed problems on ethnic minorities. Fascist regimes suppressed other political parties, protests, and independent trade unions. They justified violence to achieve their goals and were strongly anticommunist. Germany turned to fascism (see Topic 7.6), and some other countries did as well.

Rise of Fascism in Italy Benito Mussolini coined the term fascism, which comes from the term fasces, a bundle of sticks tied around an axe, which was an ancient Roman symbol for authority. This symbol helped characterize Italy’s Fascist government, which glorified militarism and brute force.

The Italian fascist state was based on a concept known as corporatism, a theory based on the notion that the sectors of the economy—the employers, the trade unions, and state officials—are seen as separate organs of the same body. Each sector, or organ, was supposedly free to organize itself as it wished as long as it supported the whole. In practice, the fascist state imposed its will upon all sectors of society, creating a totalitarian state—a state in which the government controls all aspects of society.

Mussolini Takes Control Even though Italy had been considered one of the victors at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference—along with Britain, France, and the United States—Italy received very little territory from the Treaty of Versailles. This failure to gain from the war caused discontent in Italy. Amid the general bitterness of the 1920s, Mussolini and his allies in the Fascist Party managed to take control of the parliament. Mussolini became a dictator, repressing any possible opposition to his rule. Militaristic propaganda infiltrated every part of the Fascist government. For example, schoolchildren were taught constantly about the glory of their nation and their fearless leader, “Il Duce.”

Part of Mussolini’s fascist philosophy was the need to conquer what he considered an inferior nation. During the imperialist “Scramble for Africa” in the 19th century, Italy seized Libya and colonized Italian Somaliland, now part of Somalia. However, the Italian army was pushed back by Abyssinia, modern-day Ethiopia, in the 1890s. In 1934, Mussolini called for the complete conquest of Abyssinia. In 1935, 100,000 Italian troops crossed the border from Somaliland to Abyssinia, defying sanctions from the League of Nations. This time, the Italian army overpowered Abyssinia’s while the global community did little to stop the conquest. Many historians believe the Abyssinian crisis destroyed the League of Nations’ credibility. In 1936, Mussolini and Germany’s Adolf Hitler formed an alliance they hoped would dominate Europe.

Fascism and Civil War in Spain After the economic decline in the early 1930s, two opposing ideologies, or systems of ideas, battled for control of Spain. The Spanish Civil War that resulted soon took on global significance as a struggle between the forces of democracy and the forces of fascism.

The Spanish Republic formed in 1931 after King Alfonso VIII abdicated. In 1936, the Spanish people elected the Popular Front, a coalition of left- wing parties, to lead the government. A key aspect of the Front’s platform was land reform, a prospect that energized the nation’s peasants and radicals. Conservative forces in Spain, such as the Catholic Church and high-ranking members of the military, were violently opposed to the changes that the Popular Front promised. In July of the same year, Spanish troops stationed in Morocco conducted a military uprising against the Popular Front. This action marked the beginning of the Spanish Civil War, which soon spread to Spain itself. General Francisco Franco led the insurgents, who called themselves Nationalists. On the other side were the Republicans or Loyalists, the defenders of the newly elected Spanish Republic.

Foreign Involvement Although the nations of Europe had signed a nonintervention agreement, Hitler of Germany, Mussolini of Italy, and Antonio Salazar of Portugal contributed armaments to the Nationalists. Civilian volunteers from the Soviet Union, Britain, the United States, and France contributed their efforts to the Loyalists. Many historians believe that without the help of Germany, Italy, and Portugal, the Nationalist side probably would not have prevailed against the Republic of Spain.

Guernica The foreign involvement in Spain’s struggle also escalated the violence of the war. One massacre in particular garnered international attention. The German and Italian bombing of the town of Guernica in northern Spain’s Basque region was one of the first times in history an aerial bombing targeted civilians. Many historians believe that the bombing of Guernica was a military exercise for Germany’s air force, the Luftwaffe.

The tragedy of Guernica was immortalized in Pablo Picasso’s painting of that name, commissioned by the Republic of Spain and completed in 1938. Although abstract, the painting brilliantly depicts the horrific violence of modern warfare and is one of the most significant works of 20th-century art.

Franco’s Victory The Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) ended when Franco’s forces defeated the Loyalist army. He ruled Spain as a dictator until his death in 1975. Spain did not officially enter World War II (1939–1945), but the government offered some help to Germany, Italy, and Japan.

Rise of a Repressive Regime in Brazil As in Europe, parts of Latin America also became more conservative. During the interwar years, Brazil was considered Latin America’s “sleeping giant” because of its slow shift from an agricultural to an industrial economy. Large landowners dominated the nation’s economy, which frustrated members of the urban middle class. Compounding their frustration was the workers’ suffering caused by the Great Depression. Discontent led to a bloodless 1930 coup, or illegal seizure of power, which installed Getulio Vargas as president.

Vargas’s pro-industrial policies won him support from Brazil’s urban middle class. They believed he would promote democracy. However, his actions paralleled those of Italy’s corporate state under Mussolini. While Brazil’s industrial sector grew rapidly, Vargas began to strip away individual political freedoms. His Estado Novo (“New State”) program instituted government censorship of the press, abolition of political parties, imprisonment of political opponents, and hypernationalism, a belief in the superiority of one’s nation over all others and the single-minded promotion of national interests. While these policies were similar to those of European fascists, the Brazilian government did not praise or rely on violence to achieve and maintain control.

Moreover, even though Brazil had close economic ties with the United States and Germany in the late 1930s, Brazil finally sided with the Allies in World War II. This political alignment against the Axis powers made Brazil look less like a dictatorship and more liberal than it actually was. World War II prompted the people of Brazil to push for a more democratic nation later. They came to see the contradiction between fighting fascism and repression abroad and maintaining a dictatorship at home.