The Lure of Riches

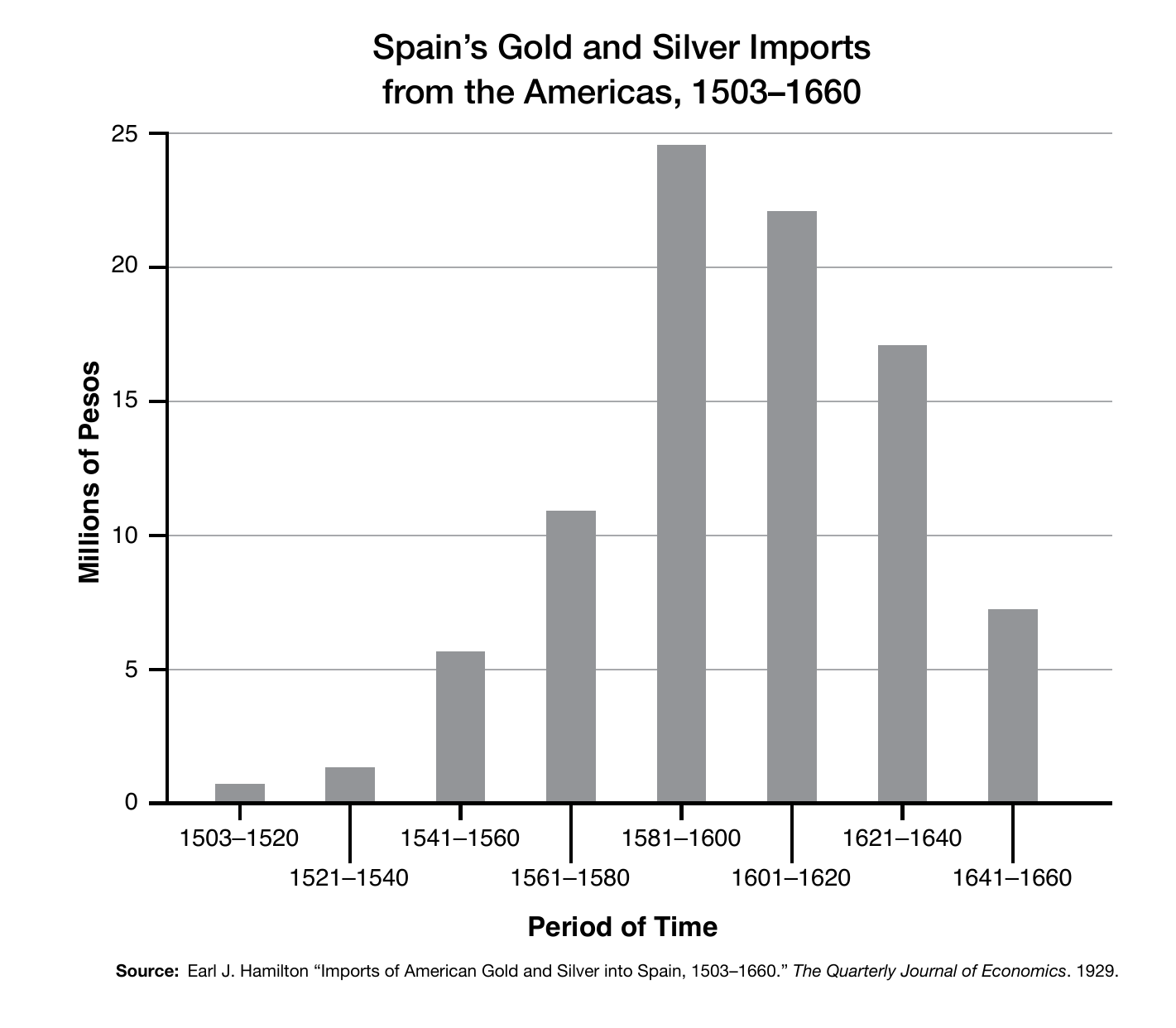

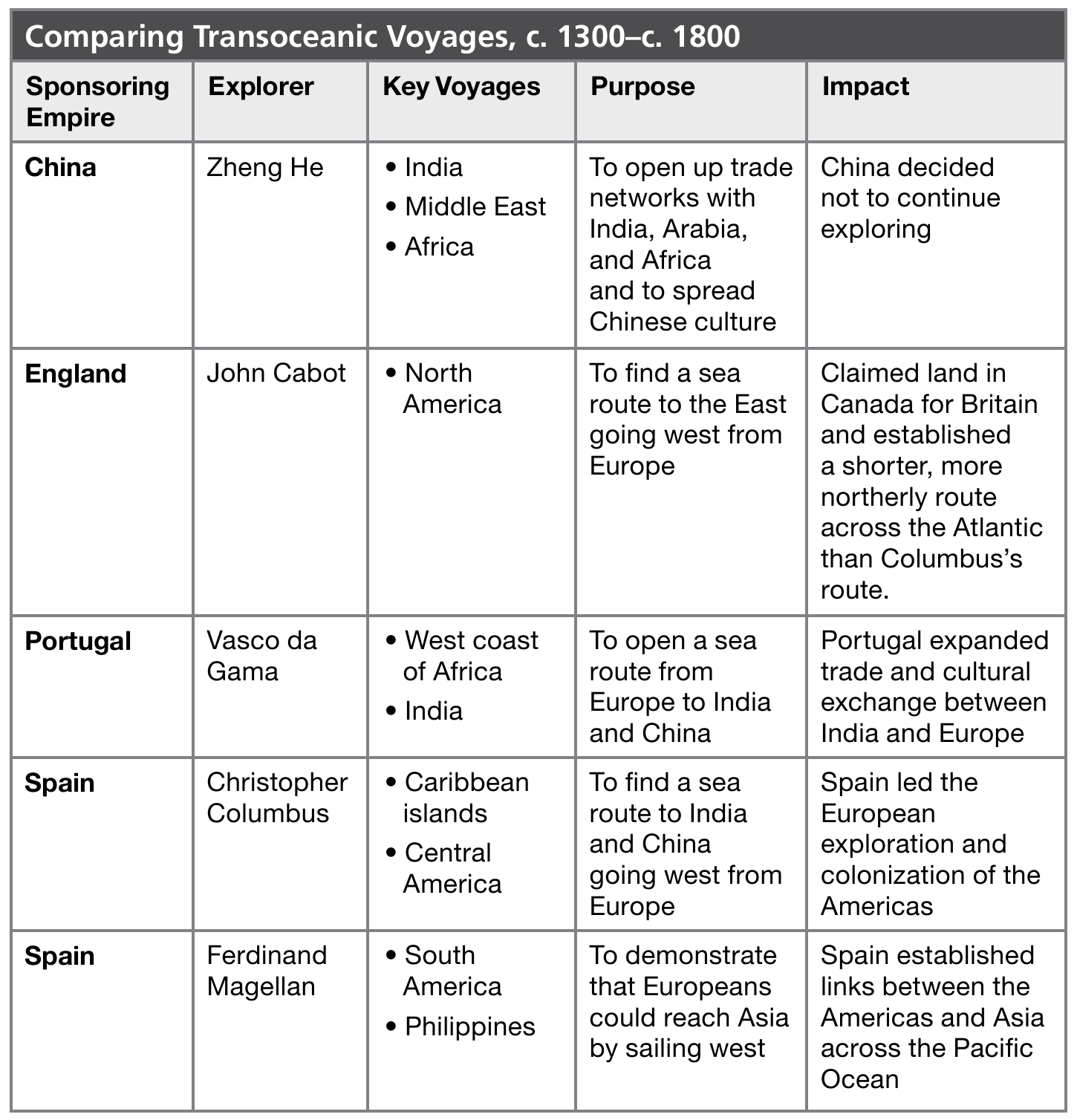

Columbus and other European explorers sought a new route to Asia and hoped to find gold, silver, and other valuable resources. The Spanish found so little of value in their first two decades of contact that they considered stopping further exploration. The English, after sponsoring voyages in the 1490s, made little attempt to explore or settle for almost a century.

However, European interest in the Americas was rekindled when the Spanish came into contact with the two major empires in the region, the Aztecs in Mesoamerica and the Incas in South America. These empires had the gold and silver that made exploration, conquest, and settlement profitable. In addition, Europeans soon realized that, by using enslaved Native Americans and later enslaved Africans, they could grow wealthy by raising sugar, tobacco, and other valuable crops.

Trade Across the Pacific China was a particularly enthusiastic consumer of this silver from the Western Hemisphere. Silver, for example, made its way from what is now Mexico across the Pacific Ocean to East Asia in heavily armed Spanish ships known as galleons that made stops in the Philippines. At the trading post in Manila, Europeans exchanged silver for luxury goods such as silk and spices, and even for gold bullion. The impressive Manila galleons allowed the silver trade to flourish. Indeed, the Chinese government soon began using silver as its main form of currency. By the early 17th century, silver had become a dominant force in the global economic system.

Spain’s rivals in Europe also explored and claimed regions in the Americas. French, English, and Dutch explorers all looked for a northwest passage—a route through or around North America that would lead to East Asia and the precious trade in spices and luxury goods.

French Exploration In the 1500s and 1600s, the French government sponsored expeditions in search of a northwest passage. In 1535, for example, French explorer Jacques Cartier sailed from the Atlantic Ocean into the St. Lawrence River at today’s northern U.S. border. He did not find a new route to Asia, but he did claim part of what is now Canada for France. Eventually, explorers such as Cartier and Samuel de Champlain (explored 1609–1616) realized there were valuable goods and rich resources available in the Americas, so there was no need to go beyond to Asia.

Like the Spanish, the French hoped to find gold. Instead, they found a land rich in furs and other natural resources. In 1608, they established a town and trading post that they named Quebec. French traders and priests spread across the continent. The traders searched for furs; the priests wanted to convert Native Americans to Christianity. The missionaries sometimes set up schools among the indigenous peoples. In the 1680s, a French trader known as La Salle explored the Great Lakes and followed the Mississippi River south to its mouth at the Gulf of Mexico. He claimed this vast region for France.

Unlike the Spanish—or the English who were colonizing the East Coast of what is now the United States—the French rarely settled permanently. Instead of demanding land, they traded for the furs trapped by Native Americans. For this reason, the French had better relations with natives than did the Spanish or English colonists and their settlements also grew more slowly. For example, by 1754, the European population of New France, the French colony in North America, was only 70,000. The English colonies included one million Europeans.

English Exploration In 1497, the English king sent an explorer named John Cabot to America to look for a northwest passage. Cabot claimed lands from Newfoundland south to the Chesapeake Bay. The English, however, did not have enough sea power to defend themselves against Spanish naval forces—although English pirates called “sea dogs” sometimes attacked Spanish ships. Then in 1588, the English surprisingly defeated and destroyed all but one third of the Spanish Armada. With that victory, England declared itself a major naval power and began competing for lands and resources in the Americas.

At about the same time the French were founding Quebec, the English were establishing a colony in a land called Virginia. In 1607, about one hundred English colonists traveled approximately 60 miles inland from the coast, where they built a settlement, Jamestown, on the James River. Both the settlement and the river were named for the ruling English monarch, James I. Jamestown was England’s first successful colony in the Americas, and one of the earliest colonies in what would become the United States. The first colonies in the present-day United States were Spanish settlements in Florida and New Mexico.

Dutch Exploration In 1609, the Dutch sent Henry Hudson to explore the East Coast of North America. Among other feats, he sailed up what became known as the Hudson River to see if it led to Asia. He was disappointed in finding no northwest passage. He and other explorers would continue to search for such a route. Though it would travel through a chilly region, it offered the possibility of being only half the distance of a route that went around South America.

Though Hudson did not find a northwest passage, his explorations proved valuable to the Dutch. Based on his voyage, the Dutch claimed the Hudson River Valley and the island of Manhattan. On the tip of this island, they settled a community called New Amsterdam, which today is known as New York City. Like many port towns, New Amsterdam prospered because it was located where a major river flowed into the ocean.

New Amsterdam became an important node in the Dutch transatlantic trade network. Dutch merchants bought furs from trappers who lived and worked in the forest lands as far north as Canada. They purchased crops from lands to the south, particularly tobacco from Virginia planters. They sent these goods and others to the Netherlands in exchange for manufactured goods that they could sell throughout colonial North America (Connect: Explain how one of the European explorers in 4.2 compares to Marco Polo. See Topic 2.5.)