Religious, Cultural, and Technological Effects of Interaction

The diffusion of different religions between c. 1200 and c. 1450 had varying effects. In some cases, the arrival of a new religion served to unify people and provide justification for a kingdom’s leadership. It often also influenced the literary and artistic culture of areas to which it spread, where themes, subjects, and styles were inspired by the spreading religion. In other places, it either fused or coexisted with the native religions. The interactions resulting from increased trade also led to technological innovations that helped shape the era.

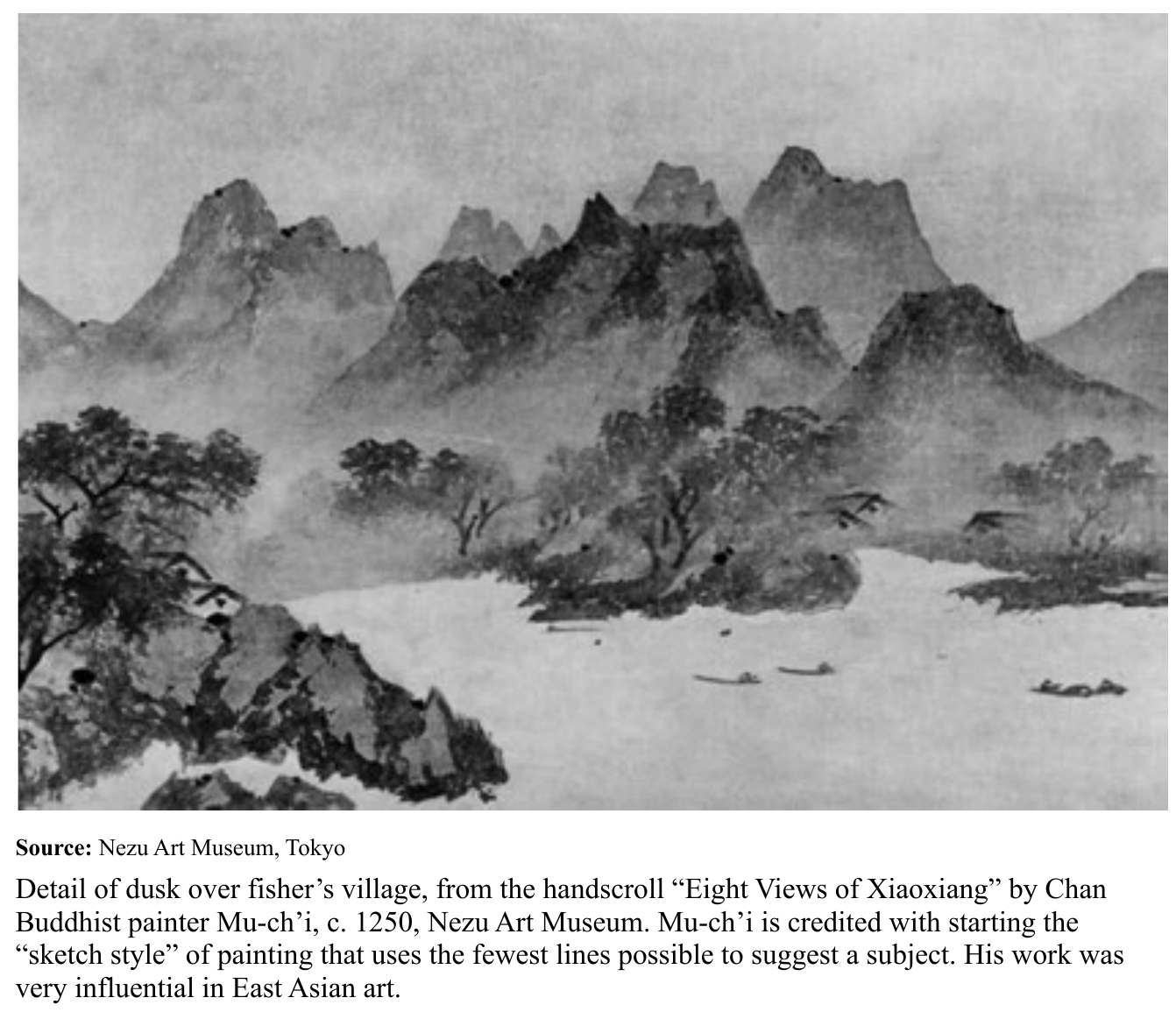

Influence of Buddhism on East Asian Culture Buddhism came to China from its birthplace in India via the Silk Roads, and the 7th-century Buddhist monk Xuanzang helped make it popular. Monks related Buddhism to familiar Daoist principles, and in time Buddhist doctrines fused with elements of Daoist traditions to create the syncretic faith Chan Buddhism, also known as Zen Buddhism. Although some leaders in China did not want China’s native religions diminished as a result of the spread of Buddhism, Chan Buddhism remained popular among ordinary Chinese citizens. Under the Song Dynasty (960–1279), many Confucians among the scholar gentry began to adopt its ideals into their daily lives. The development of printing had made Buddhist scriptures widely available to the Confucian scholar gentry. Buddhist writers also influenced Chinese literature by writing in the vernacular rather than the formal language of Confucian scholars, a practice that became widespread.

Japan and Korea, countries in China’s orbit, also adopted Buddhism, along with Confucianism. In Korea, the educated elite studied Confucian classics, while Buddhist doctrine attracted the peasants. Neo-Confucianism was another syncretic faith that originated in China, first appearing in the Tang Dynasty but developing further in the Song Dynasty. Neo-Confucianism fused rational thought with the abstract ideas of Daoism and Buddhism and became widespread in Japan and Vietnam. It also became Korea’s official state ideology.

Spread of Hinduism and Buddhism Through trade, the Indian religions of Hinduism and Buddhism made their way to Southeast Asia as well. The sea-based Srivijaya Empire on Sumatra was a Hindu kingdom, while the later Majapahit Kingdom on Java was Buddhist. The South Asian land-based Sinhala dynasties in Sri Lanka became centers of Buddhist study with many monasteries. Buddhism’s influence was so strong under the Sinhala dynasties that Buddhist priests often advised monarchs on matters of government. (See Topic 1.3.)

The Khmer Empire in present-day Cambodia, also known as the Angkor Kingdom, was the most successful kingdom in Southeast Asia. The royal monuments at Angkor Thom are evidence of both Hindu and Buddhist cultural influences on Southeast Asia. Hindu artwork and sculptures of Hindu gods adorned the city. Later, when Khmer rulers had become Buddhist, they added Buddhist sculptures and artwork onto buildings while keeping the Hindu artwork.

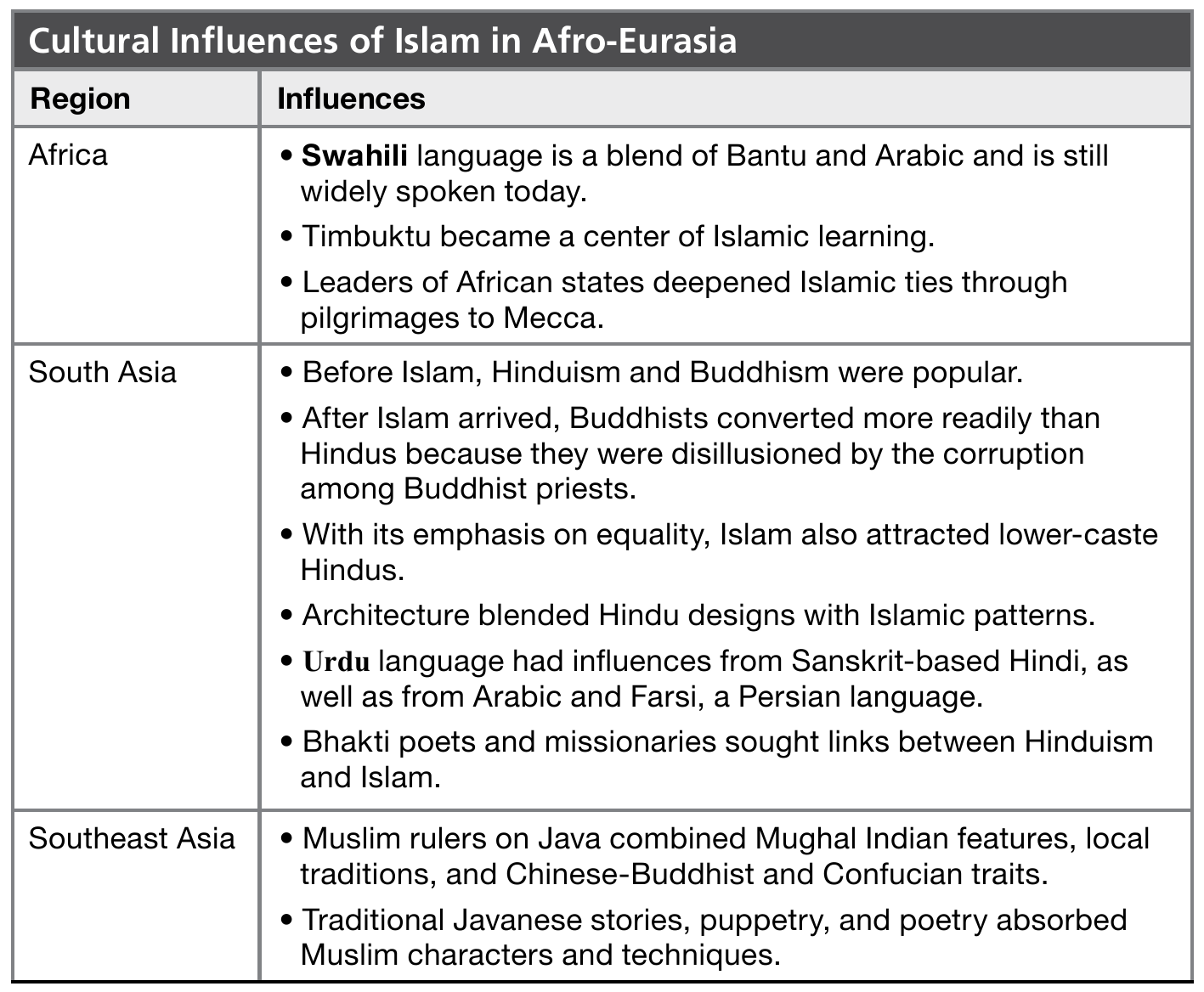

Spread of Islam Through merchants, missionaries, and conquests, Islam spread over a wide swath of Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. The chart below summarizes some of the cultural influences of that expansion.

Scientific and Technological Innovations Along with religion, science and technology traveled the trade routes. Islamic scholars translated Greek literary classics into Arabic, saving the works of Aristotle and other Greek thinkers from oblivion. Scholars also brought back mathematics texts from India and techniques for papermaking from China. They studied medicine from ancient Greeks, Mesopotamians, and Egyptians, making advances in hospital care, including surgery. (See Topic 1.2.)

Improvements in agricultural efficiency, such as the use of Champa rice, spread from India to Vietnam and China. With a reliable food supply, the population grew, as did cities and industries, such as the production of porcelain, silk, steel, and iron. Papermaking reached Europe from China in the 13th century and along with printing technology helped lead to a rise in literacy.

Seafaring technology improved with lateen sails, the stern rudder, the astrolabe, and the magnetic compass as Chinese, Indian, and Southwest Asians expanded their knowledge of astronomy and other aspects of the natural world. Production of gunpowder and guns spread from China and influenced warfare as well.

Thanks, in part, to the writing of Marco Polo, historians have a good picture of the city of Hangzhou in China. It shows how trade supported urbanization. Hangzhou was large—it was home to about one million people—but other Chinese cities were larger. Chang’an had about two million people. However, Hangzhou was the center of culture in southern China, the home of poets such as Lu Yu and Xin Qiji, and other writers and artists. Located at the southern end of the Grand Canal, it was also a center of trade. Like other important cities of the era, such as Novgorod in Russia, Timbuktu in Africa, and Calicut in India, the city grew and prospered as its merchants exchanged goods. This trade brought diversity to Hangzhou, including a thriving community of Arabs.

Other cities on the trade routes that grew and thrived included Samarkand and Kashgar. (See Topic 2.1.) They were both known as centers of Islamic scholarship, bustling markets, and sources for fresh water and plentiful food for merchants traveling the Silk Roads.

Factors Contributing to Growth of Cities

• Political stability and decline of invasions

• Safe and reliable transportation

• Rise of commerce

• Plentiful labor supply

• Increased agricultural output

Declining Cities Kashgar, however, declined after a series of conquests by nomadic invaders and in 1389–90 was ravaged by Tamerlane. (See Topic 2.2.) Another once-thriving city, the heavily walled Constantinople in present- day Turkey, also suffered a series of traumatic setbacks. Mutinous Crusader armies weakened Constantinople after an attack in the Fourth Crusade in 1204 (see Topic 1.6), and in 1346 and 1349, the bubonic plague killed about half of the people in Constantinople. After a 53-day seige, the city finally fell to the Ottomans in 1453, an event some historians believe marks the end of the High Middle Ages. (Connect: Describe the relationship between urban growth in Europe and later urban decline. (See Topic 1.6.)

Factors Contributing to Decline of Cities

• Political instability and invasions

• Disease

• Decline of agricultural productivity

Effects of the Crusades Knowledge of the world beyond Western Europe increased as Crusaders encountered both the Byzantine and Islamic cultures. The encounters also increased demand in Europe for newfound wares from the East. In opening up to global trade, however, Western Europeans also opened themselves to disease. The plague, referred to as the Black Death, was introduced to Europe by way of trading routes. A major epidemic broke out between 1347 and 1351. Additional outbreaks occurred over the succeeding decades. As many as 25 million people in Europe may have died from the plague. With drastically reduced populations, economic activity declined in Europe. In particular, a shortage of people to work on the land had lasting effects on the feudal system. Also, exposure to new ideas from Byzantium and the Muslim world would contribute to the Renaissance and the subsequent rise of secularism.