Nationalism and Unification in Europe

As nationalism spread beyond Europe, people often created an identity under one government where none had existed before. Nationalism increased in France and in other areas of Europe and in the Americas. More than in the past, people felt a common bond with others who spoke their language, shared their history, and followed their customs. Nationalism thrived in France and beyond its borders in areas conquered by Napoleon, particularly those in the Germanic areas of the declining Holy Roman Empire. Nationalism was a unifying force that not only threatened large empires, but it also drove efforts to unite people who shared a culture into one political state.

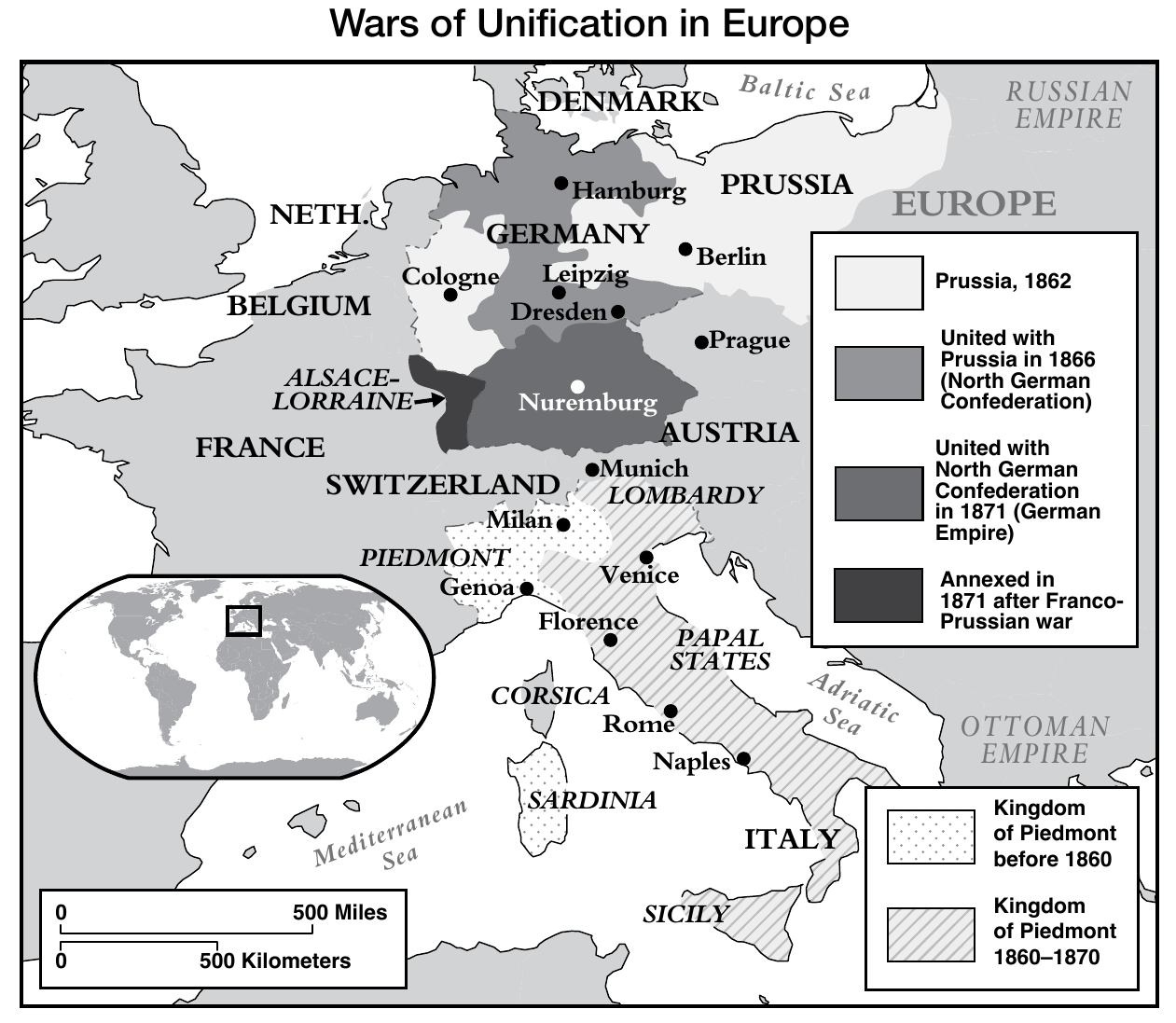

Italian Unification Count di Cavour, the prime minister of Piedmont- Sardinia, led the drive to unite the entire Italian Peninsula under the only native dynasty, the House of Savoy. At the time, the region was divided among a patchwork of kingdoms and city-states, and most people spoke regional languages rather than Italian. Cavour himself spoke French better than he spoke Italian. Like other classical liberals, he believed in natural rights, progress, and constitutional monarchy. But he also believed in the practical politics of reality, which came to be called realpolitik. Thus, he did not hesitate to advance the cause of Italian unity through manipulation. In 1858, he maneuvered Napoleon III of France into a war with Austria, hoping to weaken Austrian influence on the Italian Peninsula. Napoleon III backed out of the war after winning two important battles, partly because he feared the wrath of the Pope, who did not want his Papal States to be controlled by a central Italian government.

Nevertheless, it was too late to stop the revolutionary fervor, and soon several areas voted by plebiscite, or popular referendum, to join Piedmont (the Kingdom of Sardinia). To aid the unification effort, Cavour adopted the radical romantic revolutionary philosophy of Giuseppe Mazzini, who had been agitating for Italian resurgence (Risorgimento) since early in the nineteenth century. Cavour also allied with the Red Shirts military force led by Giuseppe Garibaldi, which was fighting farther south in the Kingdom of Naples.

German Unification In Germany, nationalist movements had already strengthened as a result of opposition to French occupation of German states under Napoleon Bonaparte. Following the Congress of Vienna, which settled the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, revolutions occurred in a number of European states, including Prussia and Austria. The revolutions of 1848 were the result of both nationalism (especially a desire for independence) and liberalism (a desire for representation under constitutions that recognized civil liberties).

Prussian leader Otto von Bismarck, who like Cavour favored realpolitik, used nationalist feelings to engineer three wars to bring about German unification. Bismarck manipulated Austria into participating in two wars, the first with Prussia against Denmark (1864) and the second between Prussia and Austria (Seven Weeks’ War of 1866). After winning both wars, Bismarck manipulated France into declaring war against Prussia. His armies beat the French soundly in the Franco-Prussian War (1870). In each of these three wars, Prussia gained territory. In 1871, Bismarck founded the new German Empire, made up of many territories gained from the wars, including Alsace-Lorraine, an area long part of France on the border between France and the new Germany.

Global Consequences By 1871, two new powers, Italy and Germany, were on the international stage in an environment of competing alliances. Balance of power would be achieved briefly through these alliances, but extreme nationalism would lead to World War I.

Unification did not solve all Italian troubles. Poverty in Italy, more in the south than in the north, led to considerable emigration in the late nineteenth century—particularly to the United States and to Argentina, where the constitution of 1853 specifically encouraged immigration, the movement of people into the country from other countries.

Balkan Nationalism The Ottoman Empire had been the dominant force in southeastern Europe for centuries. But for many reasons, the 17th century saw the beginning of its long, slow decline. A failed attempt to conquer Vienna in 1683 signaled the beginning of successful efforts by Austria and Russia to roll back Ottoman dominance in the Balkans. It was largely due to the increasing involvement and contact with Western European ideas and powers that Balkan nationalism developed.

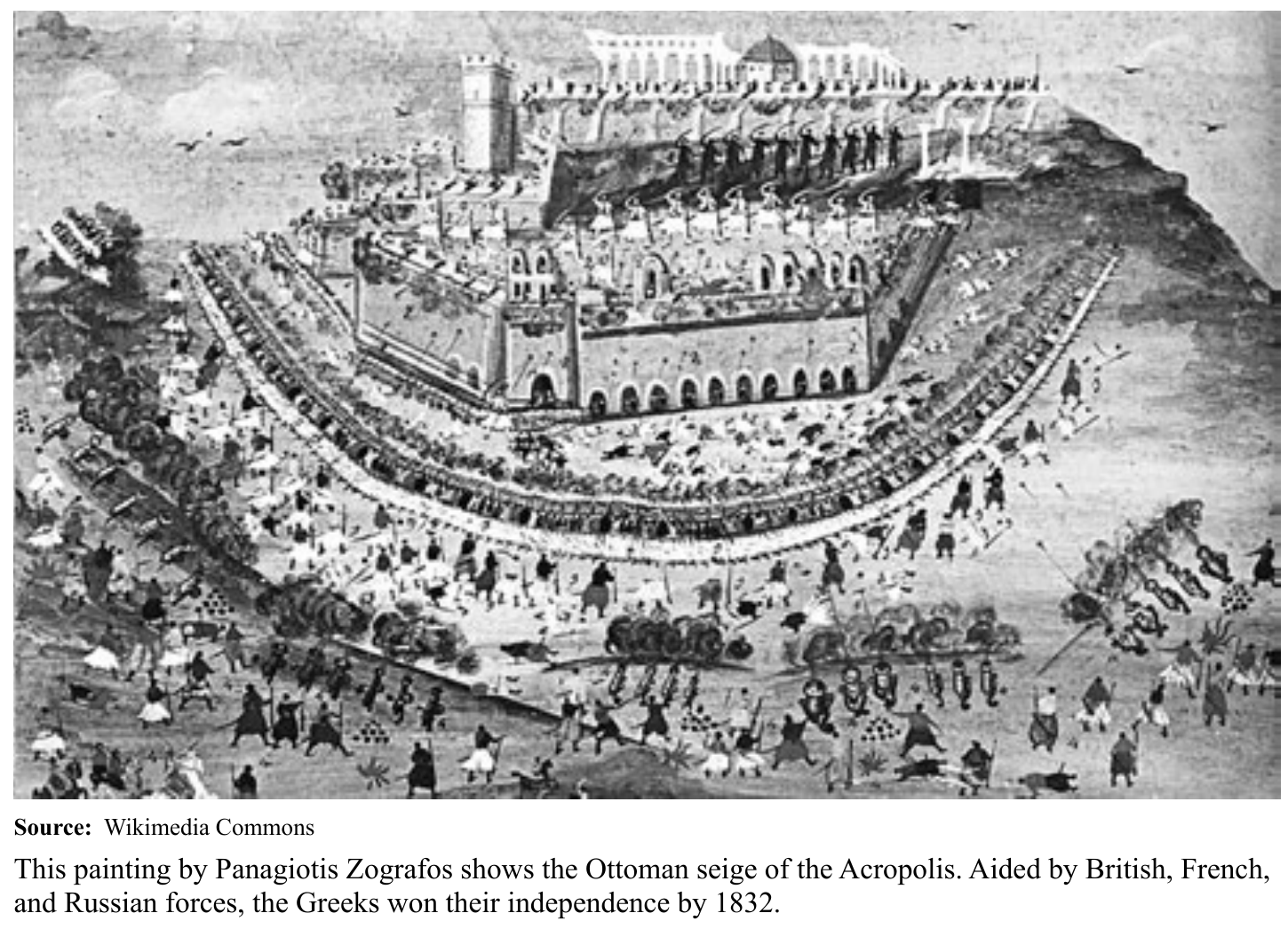

In Greece, which by 1800 had been under Ottoman control for more than 350 years, increased contact with Western ideas meant exposure to Enlightenment principles. It also meant exposure to the reverence with which Greece and its ancient culture were viewed across Europe. Together, these developments helped reawaken Greek cultural pride and stoke the fires of Greek nationalism. A protracted civil war against Ottoman forces brought some success. However, it took the intervention of a British, French, and Russian fleet, which destroyed an Ottoman fleet in 1827, to help assure Greek independence.

Events in other Balkan regions, such as Serbia, Bulgaria, and Romania, followed a similar, but by no means identical, course. The waning of Ottoman control led to greater freedom and an influx of new ideas, including nationalism. People began to rally around important cultural markers, such as language, folk traditions, shared history, and religion. Later, outside powers, such as Russia or Austria, aided in achieving independence.

Ottoman Nationalism The 1870s and 1880s saw the development in the Ottoman state of Ottomanism—a movement that aimed to create a more modern, unified state. Officials sought to do this by minimizing the ethnic, linguistic, and religious differences across the empire. Taking control of local schools and mandating a standard curriculum was a major part of this drive. But the effects of nationalism were not limited to Balkan territories and Ottoman officials. Ethnic and religious groups within the Ottoman Empire had nationalist urges of their own, and they viewed Ottomanism with suspicion. Ironically, this attempt to create a more unified state actually served to highlight and intensify subject people’s feelings of difference and promote their desire for independence.

The Future of Nationalism While nationalism continues to shape how people view themselves and their political allegiances, some signs suggest that nationalism might be starting to decline. In Europe, many countries have agreed to use the same currency, to allow people to travel freely across borders, and to coordinate public policies. These changes might reflect a shift away from nationalism and toward a larger political grouping. Like city-states and empires, nations might someday give way to other forms of political organization.