Resistance to Reform in Japan

Just as China ended its long-standing civil service system, the Japanese also ended a traditional system of exercising authority. In 1871, Japan gave samurai a final lump-sum payment and legally dissolved their position. They were no longer fighting men and were not allowed to carry their swords. The bushido, their code of conduct, was now a personal matter, no longer officially condoned by the government.

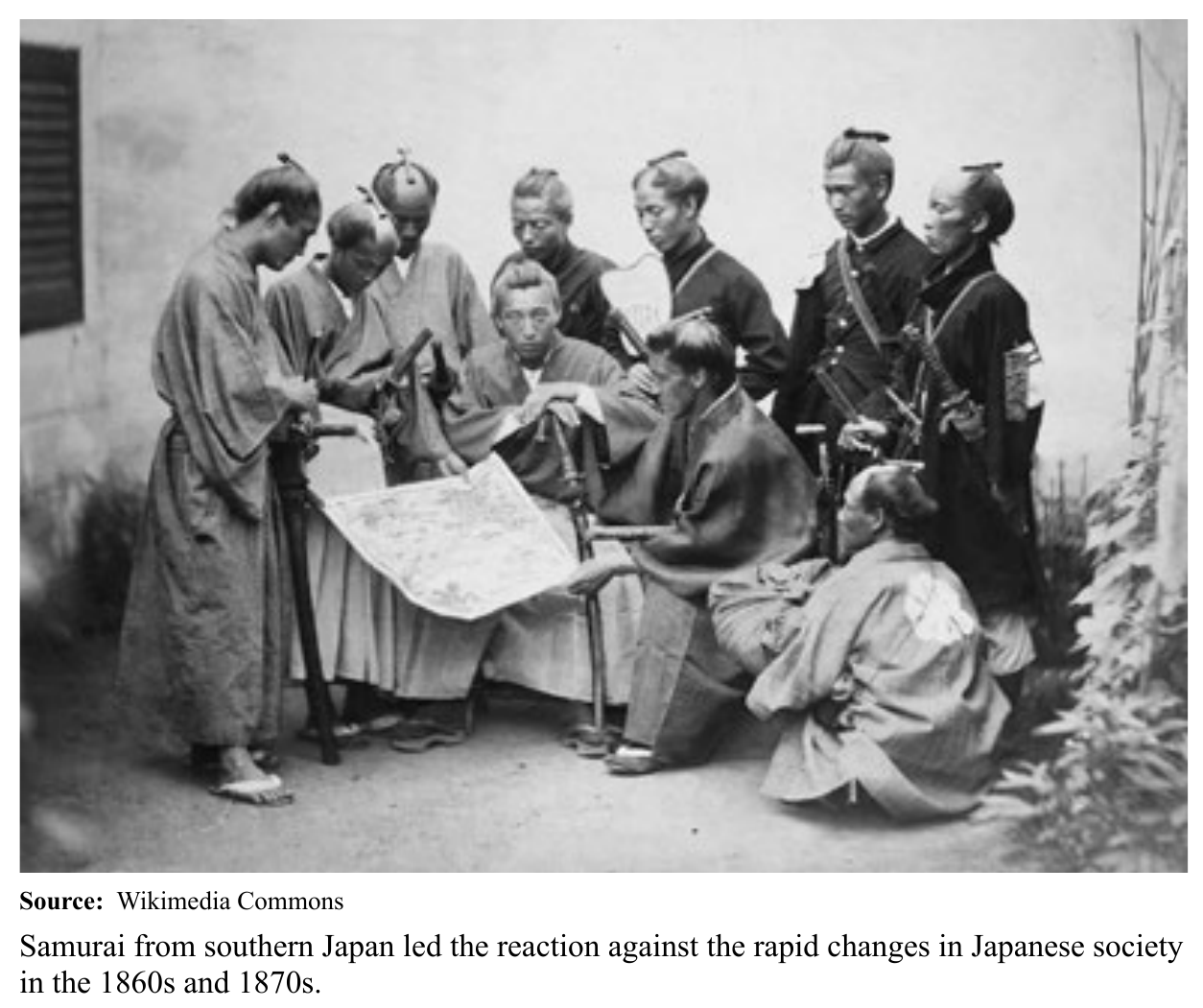

Some samurai adjusted to the change by serving the government as genros, or elder statesmen. Others, particularly those from the provinces of Satsuma and Choshu, resisted the change. They defended their right to dress and wear their hair in traditional ways and to enjoy relative autonomy from the centralized government. The last battle between the samurai shogunate forces and those loyal to the emperor occurred in the 1870s. Dismayed by defeat, the samurai became the main victims of Japan’s rapid modernization. Ironically, some of their leaders were the same people who had supported the Meiji Restoration in the 1860s.

Rise and Decline of Liberalization Some reforms in Japan worked better than others. The new schools quickly improved literacy rates, the economy rapidly industrialized, and the country began to develop traits of democracy such as a free press, strong labor unions, and respect for individual liberties. However, by the 1920s, army officers again began to dominate the government.