South Asian Movements

By the mid-19th century, sepoys, Indian soldiers under British employ, made up the majority of the British armed forces in colonial India. Most were Hindus or Muslims. In 1857, the British began using rifle cartridges that had been greased with a mixture of the fat of cows and pigs. Hindus, who view the cow as sacred, and Muslims, who refuse to slaughter pigs, were both furious. Both were convinced that the British were trying to convert them to Christianity. Their violent uprising, known as the Indian Rebellion of 1857 or the Sepoy Mutiny, spread throughout cities in northern India. The British crushed the rebellion, killing thousands, but the event marked the emergence of Indian nationalism.

After the Indian Rebellion, Britain also exiled the Mughal emperor for his involvement in the rebellion and ended the Mughal Empire. In its place, the British government took a more active role in ruling India. From 1858 until India won independence in 1947, the British Raj, the colonial government, took its orders directly from the British government in London.

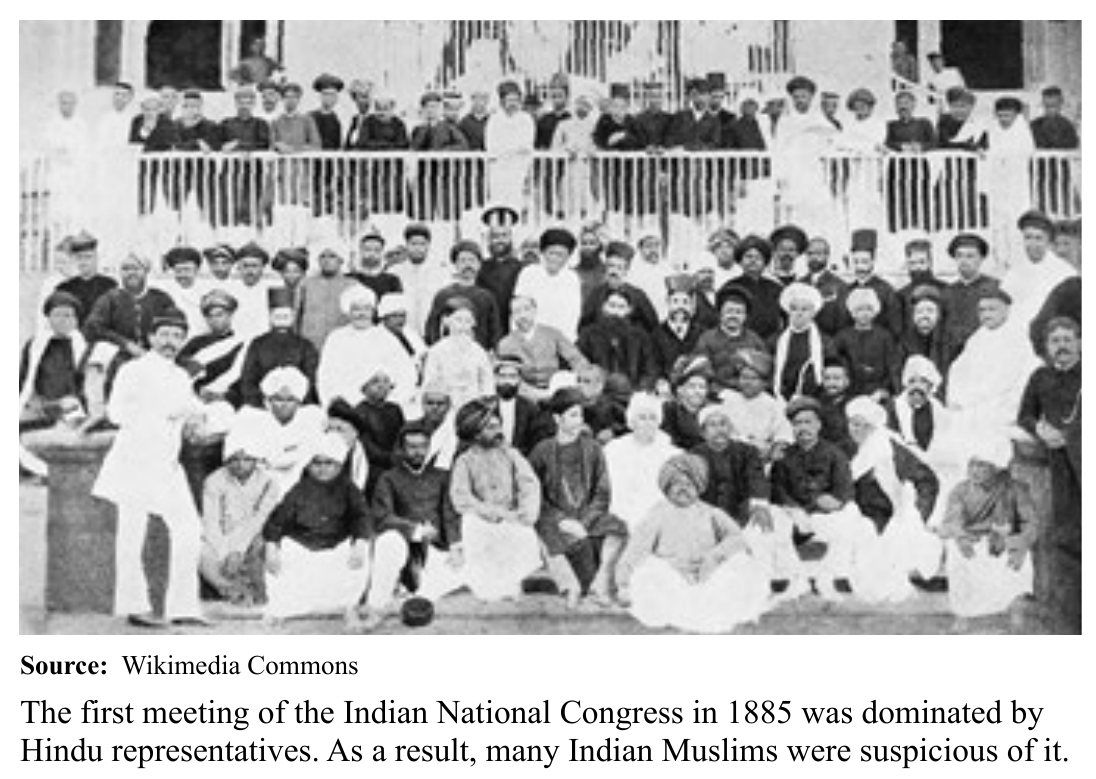

Under the Raj, many Indians attended British universities. In 1885, several British-educated Indians established the Indian National Congress. Though begun as a forum for airing grievances to the colonial government, it quickly began to call for self-rule. (Connect: Compare the motives and outcomes of the Haitian Revolution with those of the Indian Rebellion of 1857. See Topic 5.2.)