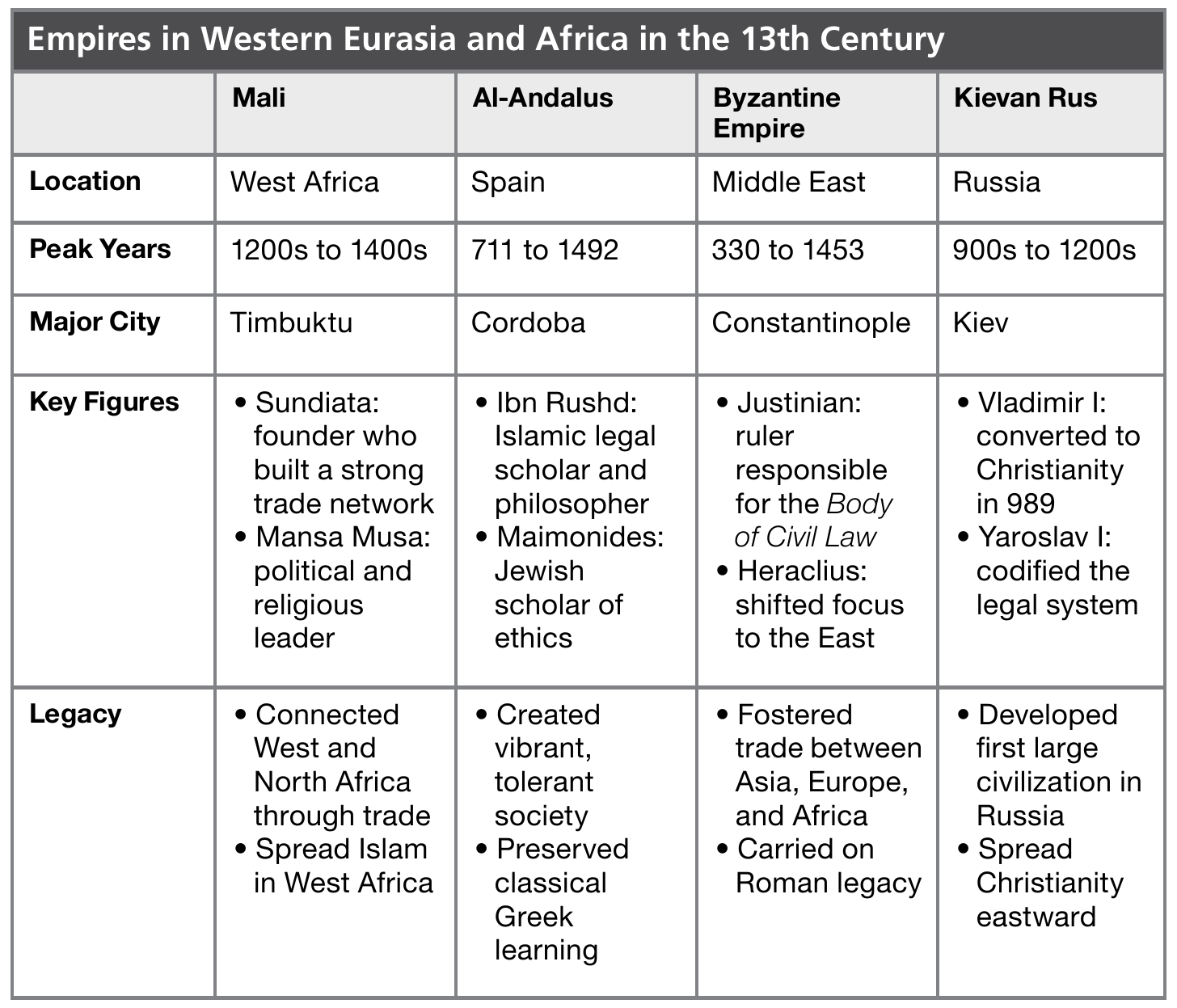

Trans-Saharan Trade

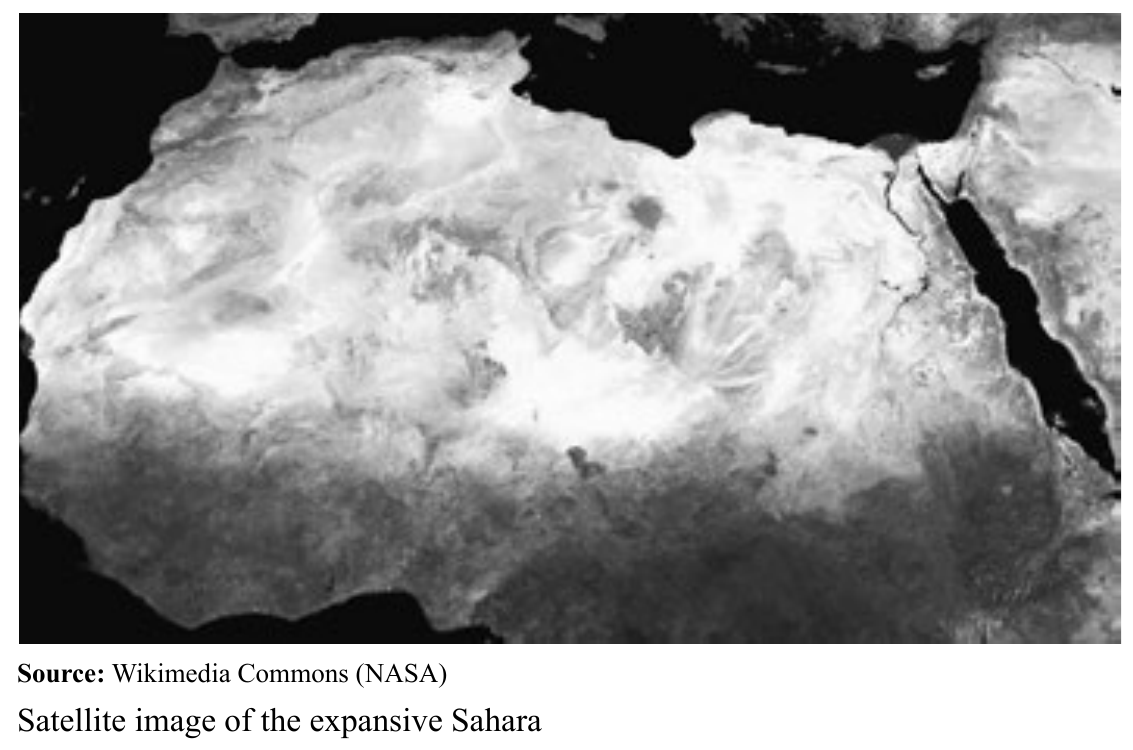

The Sahara Desert is immense, occupying 3.6 million square miles—about the same size as China. Of that vast expanse of sand and rock, only about 800 square miles are oases—places where human settlement is possible because water from deep underground is brought to the surface, making land fertile. In some oases, the water comes from underground naturally. In others, humans have dug wells to access the water.

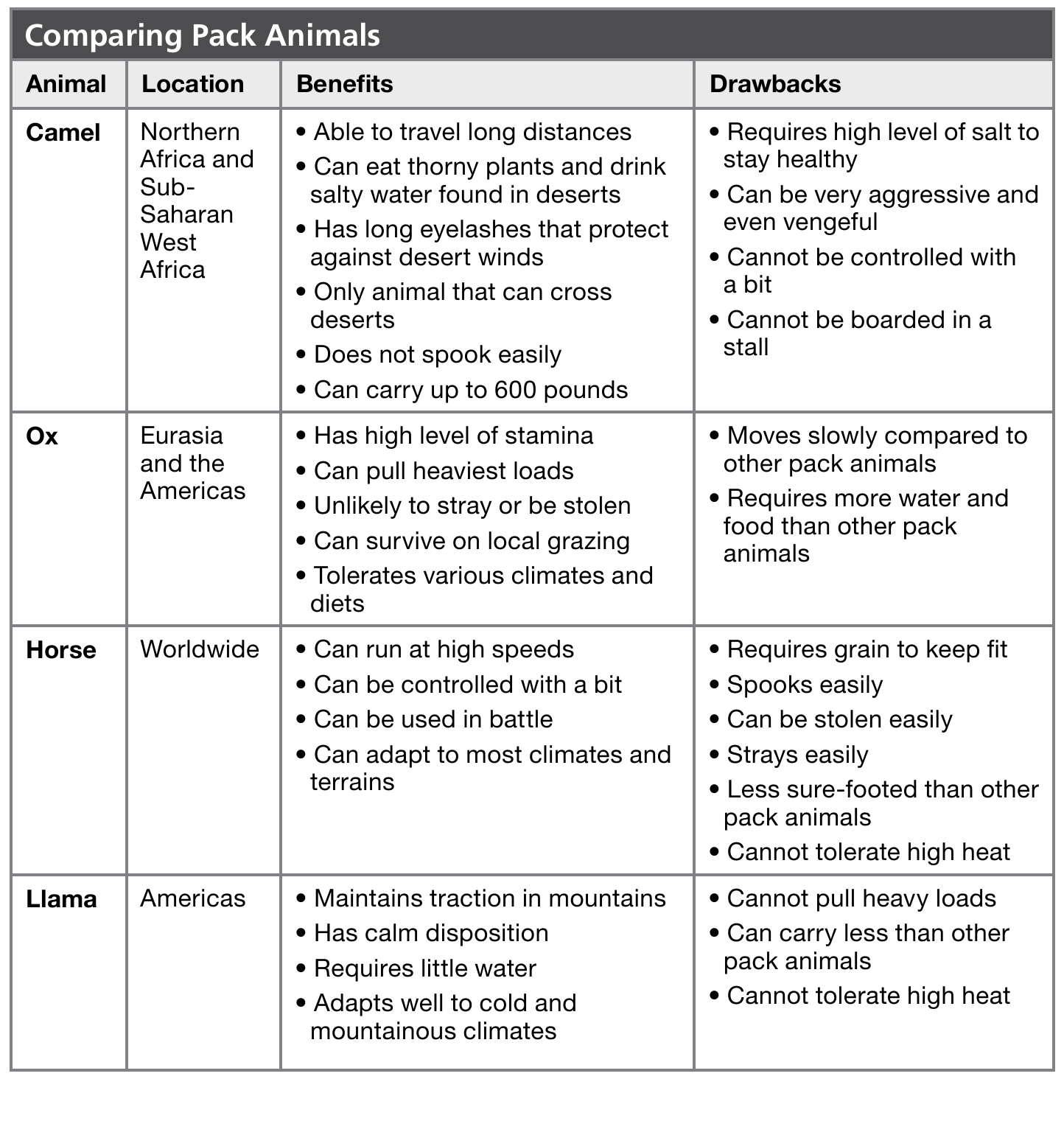

Camels, Saddles, and Trade Muslim merchants from Southwest Asia traveled across the Sahara on camels. Native to the Islamic heartland (Arabia), camels began to appear in North Africa in the 3rd century B.C.E. Accustomed to the harsh, dry climate of the Arabian Desert, camels adapted well to living in the Sahara. Compared to horses, camels can consume a large quantity of water at one time (over 50 gallons in three minutes) and not need more water for a long time. They began to replace horses and donkeys after 300 C.E.

As use of the camel spread, people developed as many as 15 types of camel saddles for different purposes. South Arabians developed a saddle in which the rider sits in back of the hump, which makes riding easier because the rider can hold onto the hair of the hump. Northern Arabians developed a saddle for sitting on top of the hump, putting them high in the air, which gave them greater visibility in battles. Being near the head gave the rider the best possible control over the camel.

However, the saddle that had the greatest impact on trade was one the Somalis in Eastern Africa developed. They were semi-nomadic and needed to carry their possessions with them, so they designed a saddle for carrying loads up to 600 pounds. Without the development of this type of saddle, camels could not have been used to carry heavy loads of goods in trade.

The caravans that crossed the Sahara often had thousands of camels laden not only with goods to trade but also with enough provisions, including fresh water, to last until the travelers could reach the next oasis. The people leading the caravans generally walked the entire way. The map on page 44 shows some of the main trade routes across the Sahara. There were seven north-south trade routes and two east-west routes. These put the people in Sub-Saharan Africa in touch with an expanding number of cultures and trading partners.

By the end of the 8th century C.E., the trans-Saharan trade had become famous throughout Europe and Asia. Gold was the most precious commodity traded. West African merchants acquired the metal from the waters of the Senegal River, near modern-day Senegal and Mauritania. Foreign traders came to West Africa seeking not only gold but also ivory and enslaved people. In exchange, they brought salt, textiles, and horses. For more than 700 years, trans-Saharan trade brought considerable wealth to the societies of West Africa, particularly the kingdoms of Ghana and Mali. They also brought Islam, which spread into Sub-Saharan Africa as a result. (Connect: Compare the impact of trade across the Sahara and throughout the Andes. See Topic 1.4.)

West African Empire Expansion

By the 12th century, wars with neighboring societies had permanently weakened the Ghanaian state. (See Topic 1.5.) In its place arose several new trading societies, the most powerful of which was Mali. North African traders had introduced Islam to Mali in the 9th century.

Mali’s Riches The government of Mali profited from the gold trade, but it also taxed nearly all other trade entering West Africa. In that way, it became even more prosperous than Ghana had been. Most of Mali’s residents were farmers who cultivated sorghum and rice. However, the great cities of Timbuktu and Gao accumulated the most wealth and developed into centers of Muslim life in the region. Timbuktu in particular became a world-renowned center of Islamic learning. By the 1500s, books created and sold in Timbuktu brought prices higher than most other goods.

Expanding Role of States The growth in trade and wealth gave rise to the need to administer and maintain it. For example, rulers needed to establish a currency whose value was widely understood. In Mali, the currency was cowrie shells, cotton cloth, gold, glass beads, and salt. Rulers also needed to protect both the trade routes and the areas where their currencies were made or harvested or their other trade resources were produced. Sometimes empires expanded their reach to take over resource-rich areas. They did so with military forces well provisioned with horses and iron weapons bought with the tax revenue. With each expansion, more people were drawn into the empire’s economy and trade networks, bringing more people in touch with distant cultures.

Mali’s founding ruler, Sundiata, became the subject of legend. His father had ruled over a small society in West Africa in what today is Guinea. When his father died, rival groups invaded, killing most of the royal family and capturing the throne. They did not bother to kill Sundiata because the young prince was crippled and was not considered a threat. In spite of his injury, he learned to fight and became so feared as a warrior that his enemies forced him into exile. His time in exile only strengthened him and his allies. In 1235, Sundiata, “the Lion Prince,” returned to the kingdom of his birth, defeated his enemies, and reclaimed the throne for himself.

Sundiata’s story made him beloved within his kingdom, but he was also an astute and capable ruler. Most scholars believe he was a Muslim and used his connections with others of his faith to establish trade relationships with North African and Arab merchants. Sundiata cultivated a thriving gold trade in Mali. Under his steady leadership, Mali’s wealth grew tremendously.

Mansa Musa In the 14th century, Sundiata’s grand-nephew, Mansa Musa, brought more fame to the region. However, Mansa Musa was better known for his religious leadership than for his political or economic acumen. A devout Muslim, Mansa Musa began a pilgrimage in 1324 to Mecca, Islam’s holiest city. His journey, however, was unlike that of any ordinary pilgrim. Mali’s prosperity allowed him to take an extraordinarily extravagant caravan to Arabia, consisting of 100 camels, thousands of enslaved people and soldiers, and gold to distribute to all of the people who hosted him along his journey. His pilgrimage displayed Mali’s wealth to the outside world.

Mansa Musa’s visit to Mecca deepened his devotion to Islam. Upon his return, he established religious schools in Timbuktu, built mosques in Muslim trading cities, and sponsored those who wanted to continue their religious studies elsewhere. Though most West Africans continued to hold onto their traditional beliefs, Mansa Musa’s reign deepened the support for Islam in Mali.

However, in fewer than 100 years after Mansa Musa’s death, the Mali kingdom was declining. By the late 1400s, the Songhai Kingdom had taken its place as the powerhouse in West Africa. Following processes like those Mali had gone through, Songhai became larger and richer than Mali. In spite of Mali’s fall, Mansa Musa’s efforts to strengthen Islam in West Africa succeeded: The religion has a prominent place in the region today.