Economic Strategies

In the 17th century, Europeans generally measured the wealth of a country in how much gold and silver it had in its coffers. To achieve this wealth, countries used economic strategies designed to sell as many goods as they could to other countries in order to obtain maximum amounts of gold and silver. To keep their wealth, countries would also spend as little of their precious metals as possible on goods from other countries.

The accumulation of capital, material wealth available to produce more wealth, in Western Europe grew as entrepreneurs entered long-distance markets. Capital changed hands from entrepreneurs to laborers, putting laborers in a better position to become consumers—and even investors, as the above quote suggests. Despite restrictions by the Church, lending money at high rates of interest became commonplace. Actual wealth also increased with gold and silver from the Western Hemisphere.

Commercial Revolution

The transformation to a trade-based economy using gold and silver is known as the Commercial Revolution. The Commercial Revolution affected all regions of the world and resulted from four key factors: the development of European overseas colonies; the opening of new ocean trade routes; population growth; and inflation, caused partly by the pressure of the increasing population and partly by the increased amount of gold and silver that was mined and put in circulation. The high rate of inflation, or general rise in prices, in the 16th and early 17th century is called the Price Revolution.

Aiding the rise of this extended global economy was the formation of joint-stock companies, owned by investors who bought stock or shares in them. People invested capital in such companies and shared both the profits and the risks of exploration and trading ventures. Offering limited liability, the principle that an investor was not responsible for a company’s debts or other liabilities beyond the amount of an investment, made investing safer.

The developing European middle class had capital to invest from successful businesses in their home countries. They also had money with which to purchase imported luxuries. The Dutch, English, and French all developed joint-stock companies in the 17th century, including the British East India Company in 1600 and the Dutch East India Company in 1602. In Spain and Portugal, however, the government did most of the investing itself through grants to certain explorers. Joint-stock companies were a driving force behind the development of maritime empires as they allowed continued exploration as well as ventures to colonize and develop the resources of distant lands with limited risk to investors.

Commerce and Finance The Dutch were long the commercial middlemen of Europe, having set up and maintained trade routes to Latin America, North America, South Africa, and Indonesia. Dutch ships were faster and lighter than those of their rivals for most of the 17th century, giving them an early trade advantage. The Dutch East India Company was also highly successful as a joint-stock company. It made enormous profits in the Spice Islands and Southeast Asia.

Source: Wikimedia

Commons

The Dutch ship

Vryburg on Chinese

export porcelain, 1756

Pioneers in finance, the Dutch had a stock exchange as early as 1602. By 1609, the Bank of Amsterdam traded currency internationally. The Dutch standard of living was the highest in Europe as such goods as diamonds, linen, pottery, and tulip bulbs passed through the hands of Dutch traders.

France and England were not so fortunate. Early in the 18th century, both fell victim to speculative financial schemes. Known as financial bubbles, the schemes were based on the sale of shares to investors who were promised a certain return on their investment. After a frenzy of buying that drove up the price of shares, the bubble burst and investors lost huge amounts of money, sending many into bankruptcy and inflicting wide damage to the economy.

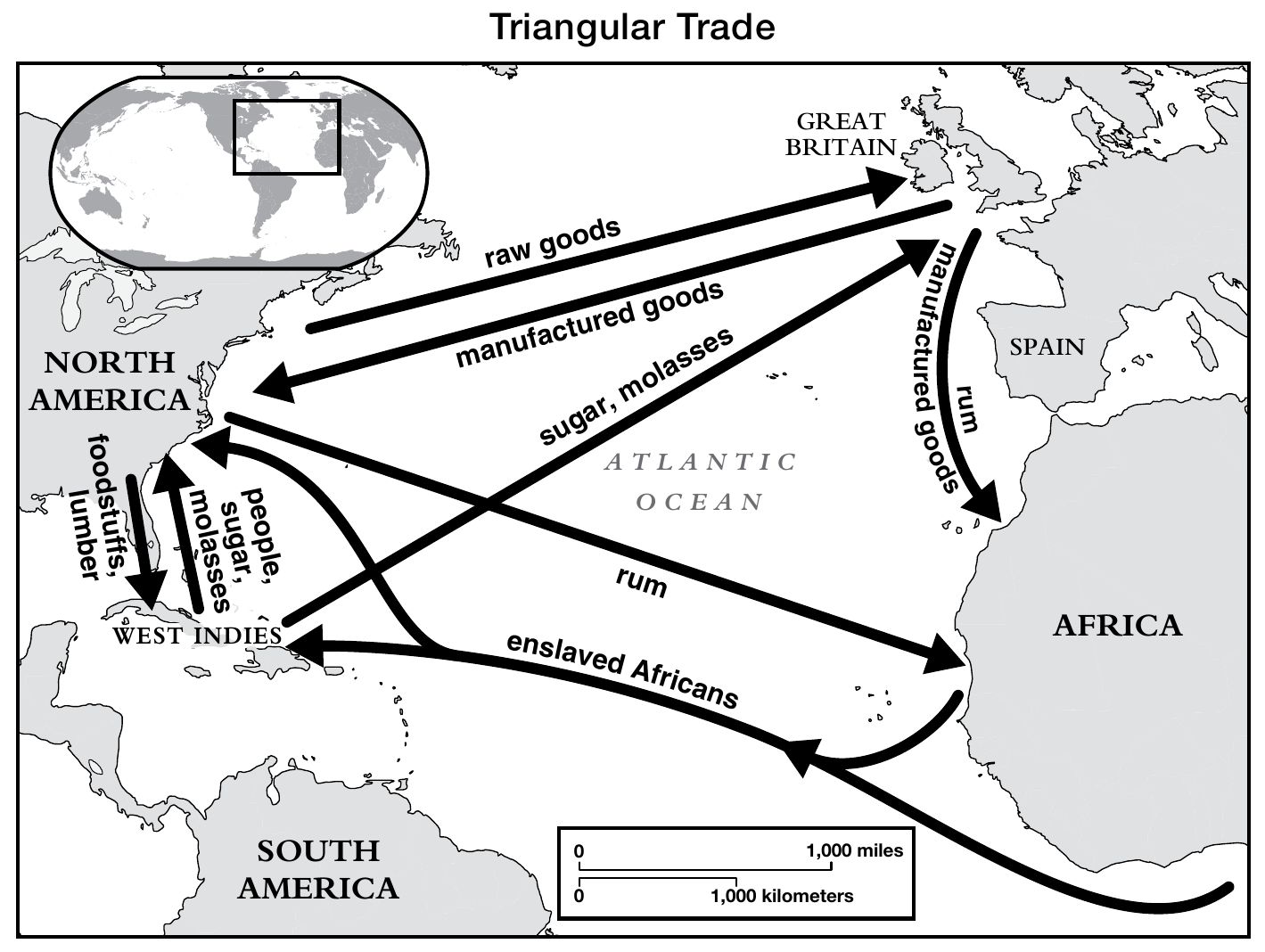

Triangular Trade The Europeans’ desire for enslaved workers in the Americas coupled with Portugal’s “discovery” of West Africa meant that Africa became the source for new labor. Enslaved Africans became part of a complex Atlantic trading system known as the triangular trade, because voyages often had three segments. A ship might carry European manufactured goods such as firearms to West Africa, and from there transport enslaved Africans to the Americas, and then load up with sugar or tobacco to take to Europe. Sugar was the most profitable good from the Americas. By the 1700s, Caribbean sugar production and rum (made from sugar) were financing fortunes in Britain, and to a lesser extent, in France and the Netherlands.

Rivalries for the Indian Ocean Trade

After Europeans stumbled on the Americas, trade over the Atlantic Ocean became significant. However, states continued to vie for control of trade routes on the Indian Ocean as well. The Portuguese soundly defeated a combined Muslim and Venetian force in a naval battle in the Arabian Sea in 1509 (see Topic 4.4) over controlling trade. They met a different fate, though, when they tried to conquer Moroccan forces in a battle on land in 1578.

Its coffers depleted after the victory, Morocco looked inland to capture the riches of the Songhai Kingdom, despite the prohibition of waging war on another Muslim state. With thousands of soldiers, camels, and horses, as well as eight cannons and other firearms, Moroccan forces traveled months to reach Songhai. In 1590, in a battle near Gao, the Songhai—despite their greater number of fighters—were overcome by the force of firearms. The empire crumbled. The Spanish and Portuguese soon overtook much of this territory.