Disease and Poverty

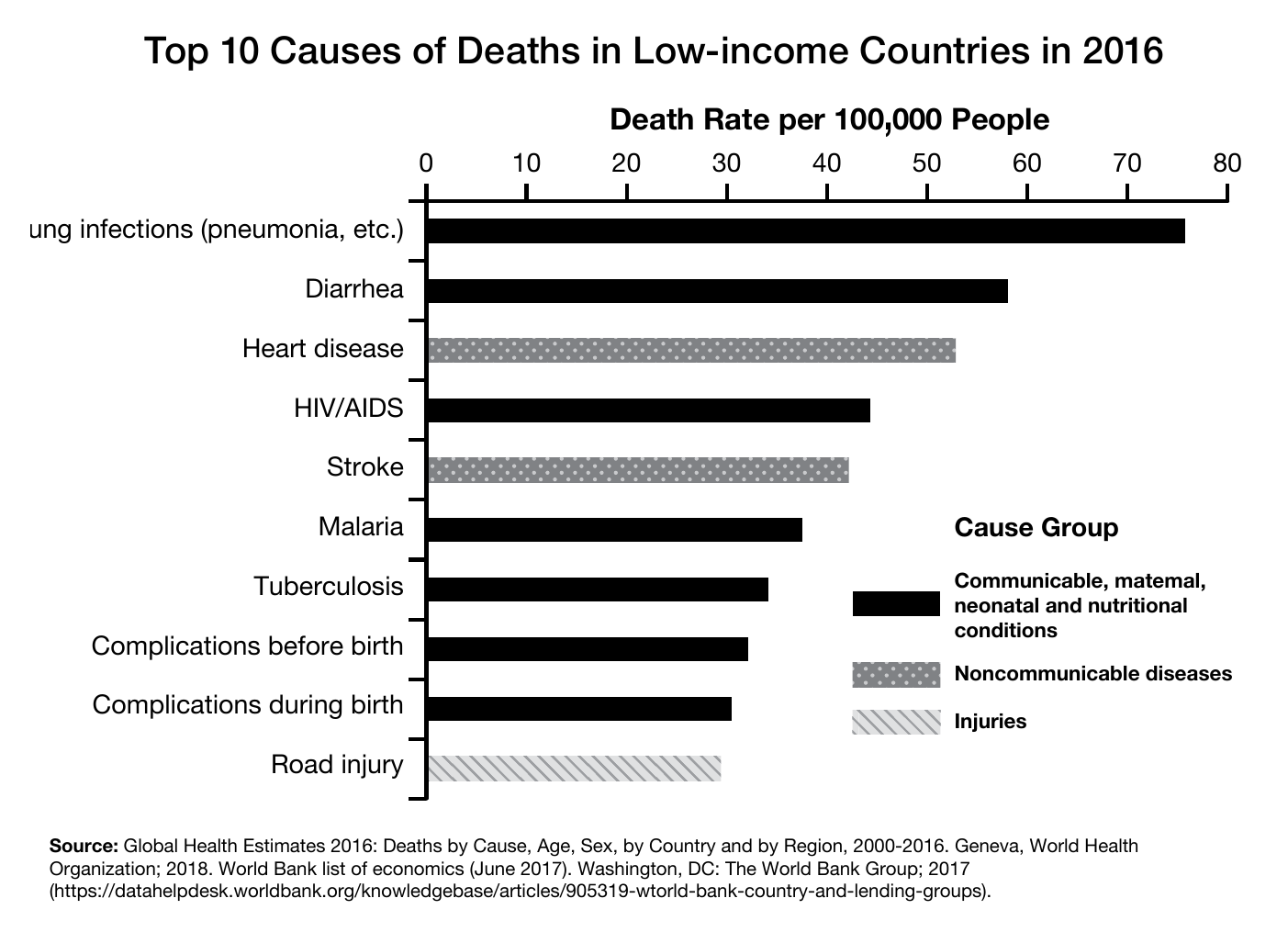

Even when cures exist, some diseases persist because the conditions of poverty are contributing factors. Poor housing or working conditions, contaminated water, and lack of access to health care are commonplace among populations with low incomes, and they all contribute to the spread of disease.

Malaria A parasitic disease spread by mosquitoes in tropical areas, malaria killed more than 600,000 people each year in the early 21st century. Most of these were young African children. The international non-governmental organization (NGO) Doctors Without Borders treated about 1.7 million people annually. Experts developed preventive approaches, such as distributing mosquito nets treated with insecticide as cover during sleep. However, people can still become infected during waking hours. A vaccine for malaria has been in development for many years, but one that is effective in most cases is still in trials. Nonetheless, progress has been made. In 2019, the World Health Organization certified Algeria and Argentina as malaria-free. The organization cautioned, however, that some types of mosquitoes were becoming resistant to insecticides.

Tuberculosis Another disease associated with poverty is tuberculosis (TB), an airborne infection that spreads through coughs and sneezes and affects the lungs. Before 1946, no effective drug treatment was available for this deadly disease. Then a cure was developed involving antibiotics and a long period of rest. In countries where TB is common, vaccines are administered to children. In the early 21st century, a strain of tuberculosis resistant to the usual antibiotics appeared. The number of infected patients increased, especially in prisons, where people live in close quarters. The WHO began a worldwide campaign against tuberculosis in the 2010s.

Cholera A bacterial disease that spreads through contaminated water, cholera causes about 95,000 deaths per year. Like tuberculosis and malaria, cholera affects mainly poor people in developing countries. Methods to counter cholera include boiling or chlorinating drinking water and washing hands. Although cholera vaccines are available, they do not reduce the need to follow these preventive measures. A severe cholera infection can kill within a few hours, but quickly rehydrating an exposed person can effectively eliminate the risk of death.

Polio Another disease caused by water contaminated by a virus transmitted in fecal matter, polio once infected 100,000 new people per year. It could result in paralysis and sometimes death. The world cheered when an American researcher, Jonas Salk, announced on April 12, 1955, that an injectable vaccine against polio had proven effective. Six years later, an oral vaccine, developed by Albert Sabin, became available.

Vaccines became the centerpiece of a global public health campaign to eliminate polio. A joint effort by governments, private organizations, and United Nations agencies began in 1988. In less than 30 years, polio was eliminated in all but a few countries. In places where it still exists, such as Pakistan and Afghanistan, war makes administering the vaccine difficult. Political unrest and religious fundamentalism make people fearful of programs advocated by outsiders. Still, the success of the campaign showed that coordinated global efforts could help solve global problems. (Connect: Compare the effects of diseases during the Age of Exploration to those in the 20th century. See Topic 4.3.)