Unit 5 AP Exam Practice

Document-Based Questions

1. Using the documents and your knowledge of world history, evaluate the extent to which the roles of women in Japan and Argentina were similar or different in the period from the 1850s to the 1920s.

Document 1

Document 1

Source: P. F. Siebold, Manners and Customs of the Japanese in the Nineteenth Century, 1852.

The position of women in Japan is apparently unlike that of the sex in all other parts of the East, and approaches more nearly their European condition. The Japanese women are subjected to no jealous seclusion, hold a fair station in society, and share in all the innocent recreations of their fathers and husbands. The minds of the women are cultivated with as much care as those of men; and amongst the most admired Japanese historians, moralists, and poets are found several female names. But, though permitted thus to enjoy and adorn society, they are, on the other hand, [kept in] complete dependence on their husbands, sons, or other relatives. They have no legal rights, and their evidence is not admitted in a court . . . At home, the wife is the mistress of the family; but in other respects she is treated rather as a toy for her husband’s amusement, than as the rational, confidential partner of his life.

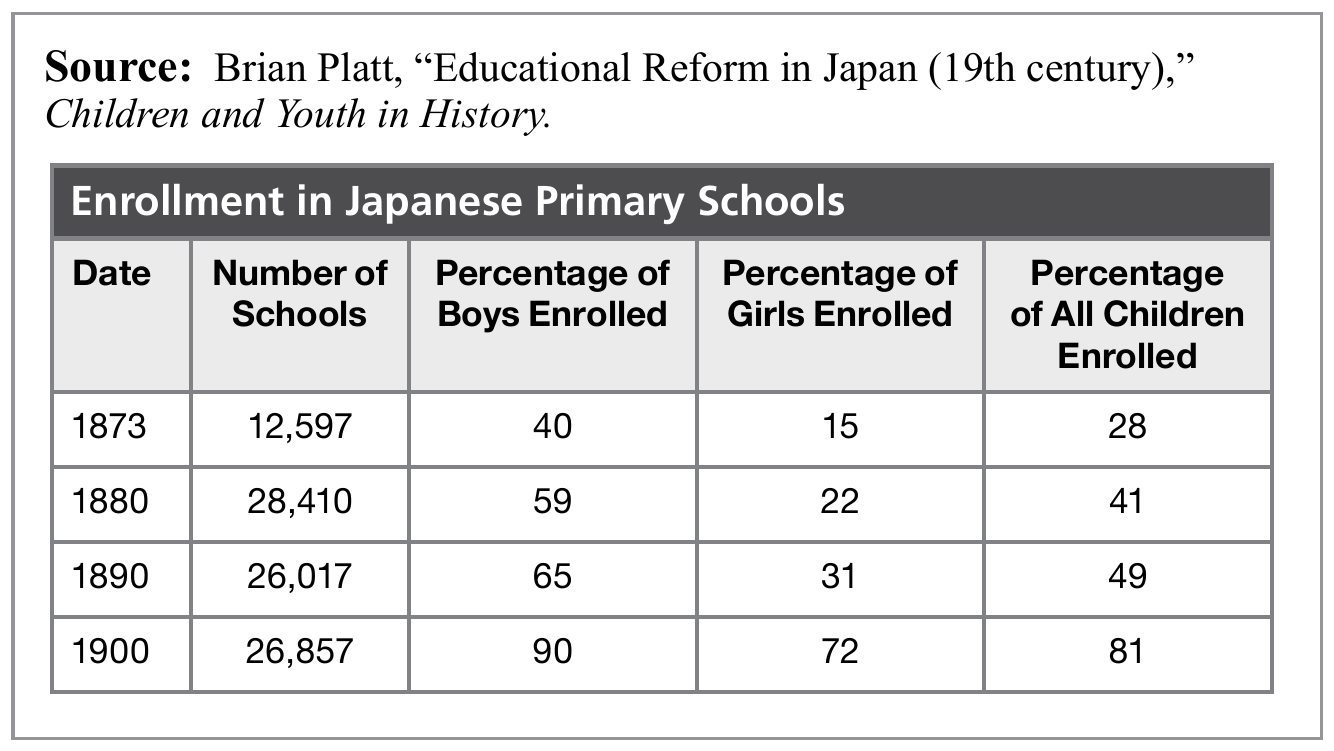

Document 2

Document 2

Document 3

Document 3

Source: Baron Kikuchi, minster in the Japanese government, speech in 1907.

Our female education, then, is based on the assumption that women marry, and that its object is to fit girls to become good wives and wise mothers. . . . The house was, and still is, . . . the unit of society, not the individual . . . the object . . . of female education—in a word, to fit girls to become good wives and mothers, proper helpmates and worthy companions of the men of Meiji, and noble mothers to bring up future generations of Japanese.

Document 4

Document 4

Source: Journalist describing the lives of female silk workers in Japan, 1898.

When I encountered silk workers I was even more shocked than I had been by the situation of weaving workers.… At busy times they go straight to work on rising in the morning, and not infrequently work through until 12:00 at night. The food is six parts barley to four parts rice. The sleeping quarters resemble pigsties, so squalid are they. What I found especially shocking is that in some districts, when business is slack, the workers are sent out into service for a fixed period, with the employer taking all their earnings… Many of the girls coming to the silk districts pass through the hands of recruiting agents. In some cases they may be there for two to three years and never even know the name of the neighboring town. The local residents think of those who have entered the ranks of the factory girls in the same manner as tea house girls, bordering on degradation. If one had to take pity on just one group among all these workers, it must be first and foremost the silk workers.

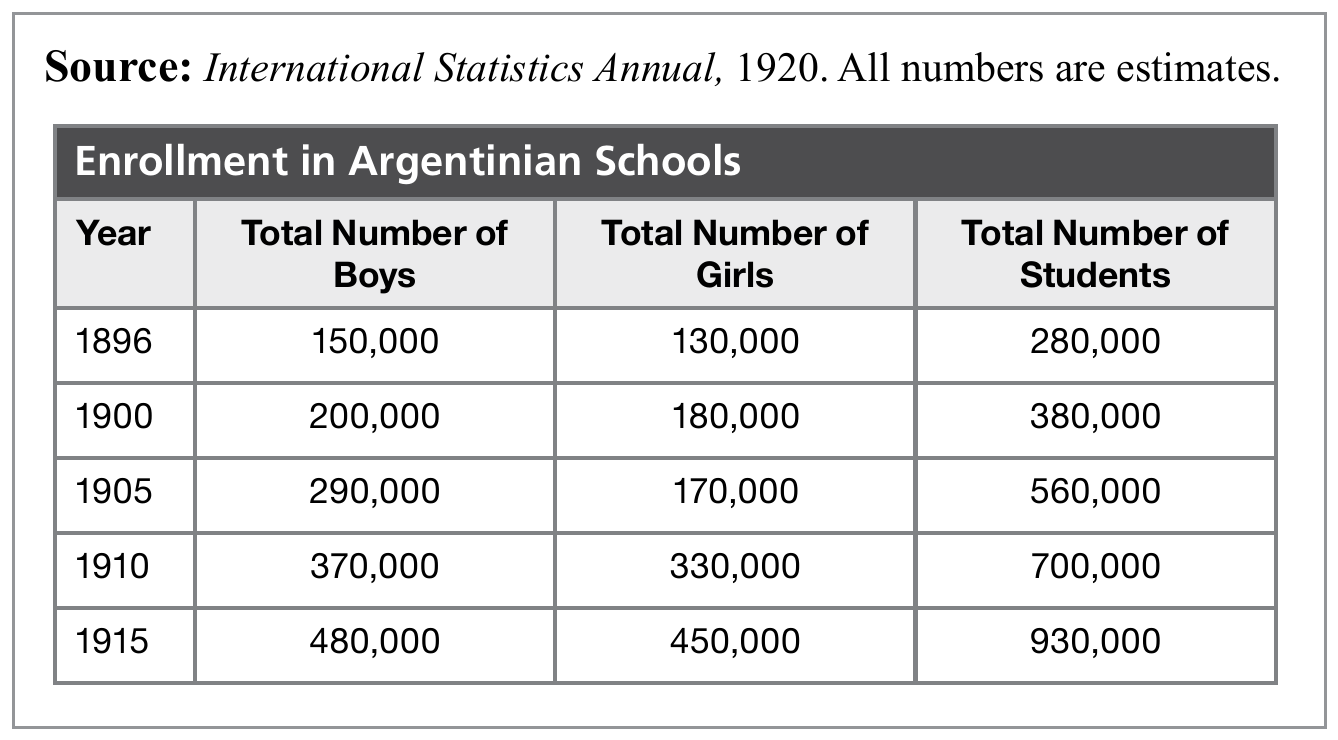

Document 5

Document 5

Document 6

Document 6

Source: Josefina Pelliza de Sagasta, “Women Dedicated to Miss Maria Eugenia Echenique,” 1876.

Women should be educated; give them a solid education, based on wholesome principles, cemented with moral and sensible beliefs; they should have a general knowledge of everything that awakens ingenuity and determines ideas, but not for them are the calculation and egotism with which they instruct English women, not for them the ridiculous ideas of North American women who pretend in their pride to be equal to men, to be legislators and obtain a seat in Congress or be university professors, as if it were not enough to be a mother, a wife, a housewife, as if her rights as a woman were not enough to be happy and to make others happy, as if it were not enough to carry out her sacred mission on earth: educating her family, cultivating the tender hearts of her children making them useful citizens, laborers of intelligence and progress, with her words and acts, cultivating love in her children and the sentiments that most enhance women: virtue, modesty and humility. Girls, women someday, be tender and loving wives, able to work for the happiness of your life’s partner instead of bringing about his disgrace with dreams and aspirations beyond your sphere.

Document 7

Document 7

Source: Maria Eugenia Echenique, writing in response to Josefina Pelliza de Sagasta, 1876.

Every day we see men with unscrewed-on heads who have no love for order nor true affection for their families, who spend their lives on gambling and rambling around; cold-bloodedly, they leave their children on the street, because their wives, whose sphere of action is reduced only to love and suffering, do not know how to oppose forcefully the squandering nor how to stop in time the abuses from their husbands nor save in this way the interests of their children.

Emancipation protects women from this catastrophe. A woman, educated in the management of business, even if she does not make a profession of it, knows how to prevent or remedy the problem once it has occurred. She does not go through the pain of seeing her children begging for bread from door to door, because she has a thousand resources to satisfy their needs honorably. She goes to work, and thus she raises her children without the need for others’ support that could lead her to corruption and to spend a miserable and humiliating life. Love can dry tears and sweeten the bitterness of life, but it cannot satisfy hunger nor cover nakedness. Love cannot be developed on a sublime and heroic level unless one is prepared to work, to put sentiment into practice.

Emancipation, conceding to women great rights, instills in them a great heart that takes them closer to the true perfection to which men can aspire here on earth. A woman who, to her physical beauty and spirituality, adds education and the ability to act for good in her vast sphere, is the ideal type imagined by Christianity, and she is going to carry out progress in this century.

Long Essay Questions

1. In the 1800s and early 1900s, industrialization transformed societies in Africa and Asia, but the process of industrialization varied from country to country.

Develop an argument that evaluates the extent to which the process of industrialization in Egypt under Muhammad Ali and in Japan during the Meiji Era were similar or different.

2. Enlightenment ideals and the concept of nationalism swept the Atlantic world from 1750 to 1900 as people developed new standards of freedom and self-determination.

Develop an argument that evaluates the extent to which intellectual and ideological causes influenced the revolutions that occurred in the Atlantic world during that era.

3. New inventions contributed greatly to industrialization from 1750 to 1900 in Eurasia, Africa, and the Americas, but agricultural productivity and natural resources also played a part.

Develop an argument that evaluates the extent to which environmental factors contributed to industrialization from 1750 to 1900.

4. In the period from 1750 to 1900, businesses in Eurasia, the Americas, and Africa developed new technologies and new types of business organizations.

Develop an argument that evaluates the extent to which the technologies and types of business organizations in Russia, the United States, and China were similar or different from 1750 to 1900.