Prejudice and Regulation of Immigration

In the United States and Australia, native-born residents resented immigrants from China who were willing to work for lower wages. In response to these resentments, governments institutionalized discrimination against the Chinese.

Regulation in the United States

Nativists were powerful enough in California that a revised constitution ratified in 1879 included several provisions that targeted people from China:

• It prohibited the state, counties, municipalities, and public works from hiring Chinese workers.

• It prevented individuals from China, and any others who were not considered white, from becoming citizens on the grounds that they were “dangerous to the well-being of the State.”

• It encouraged cities and towns either to remove Chinese residents from within their limits or to segregate them in certain areas.

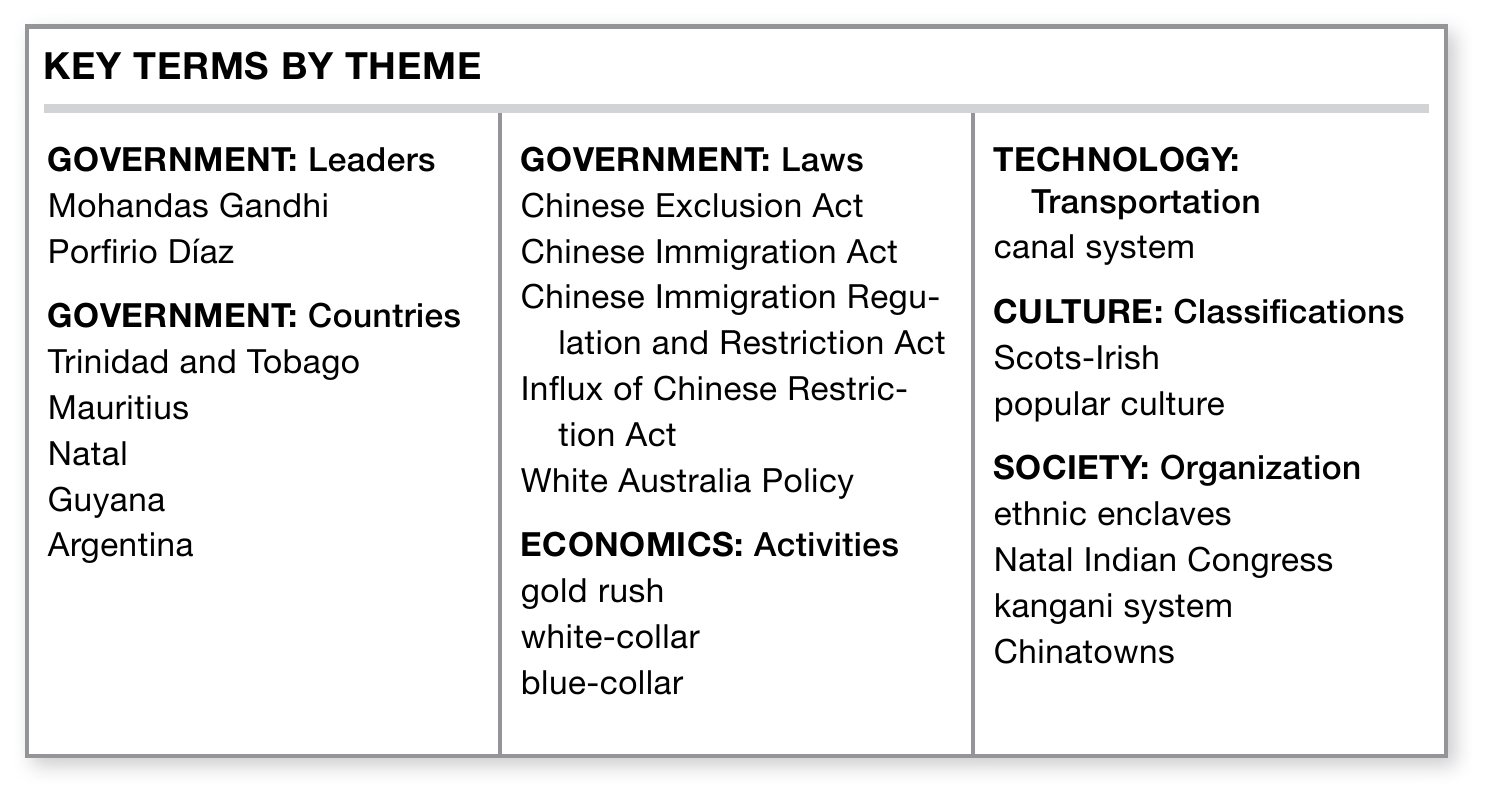

With many thousands of Chinese living in the United States by 1882, Congress banned further Chinese immigration by passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act. Initially limited to a ten year period, the policy was extended periodically and made permanent in 1902. This act, which was finally repealed in 1943, showed the discrimination in the United States.

After the U.S. Congress excluded Chinese immigrants, some of them began to move to Mexico. Mexican President Porfirio Díaz promoted immigration as well as development, especially in the northern area bordering the United States. Rather than working as laborers in the mines or railroads, most worked as truck farmers, shopkeepers, or manufacturers.

White Australia

Before the Australian gold rushes of the 1850s and 1860s, most of the Chinese in Australia were indentured laborers, convicts, or traders. During the gold rushes, the Chinese population grew to around 50,000. In response to the influx of Chinese miners, the parliament of the province of Victoria passed a Chinese Immigration Act in 1855 that limited the number of Chinese who could come ashore from each ship. Many Chinese got around this law by landing instead in South Australia.

In December 1860, white miners in the goldfields of New South Wales attacked the area where Chinese miners were quartered, killing several and wounding many others. Several other attacks followed. One of the worst occurred on June 30, 1861, when several thousand white miners attacked the Chinese and plundered their dwellings.

In response to this violence, the New South Wales Legislative Council passed the Chinese Immigration Regulation and Restriction Act in November of that year. The act, eventually repealed in 1867, was an attempt to restrict the number of Chinese immigrants from entering the colony. By the end of the gold rushes in 1881, New South Wales passed the Influx of Chinese Restriction Act, which attempted to restrict Chinese immigration by means of an entrance tax.

After the gold rushes, the Chinese in Australia turned to other sources of income, such as gardening, trade, furniture making, fishing, and pearl diving. While Chinatowns (Chinese enclaves) developed in cities across Australia, the Chinese made their biggest economic contributions in the Northern Territory and north Queensland regions. Eventually, however, anti-Chinese sentiment grew. Because the Chinese artisans and laborers would work for less than white Australians, resentment increased. Anti-Chinese leagues also began to develop.

Although the number of Chinese in Australia was declining, they were becoming more concentrated in Melbourne and Sydney and thus more visible. After six separate British self-governing colonies in Australia united under a single centralized government in 1901, the new parliament took action to limit non-British immigration. The new attorney general stated that the government’s policy was to preserve a “white Australia.” The White Australia Policy, as it was known, remained in effect until the mid-1970s.(Connect: Compare the experiences in Australia of Chinese and Japanese immigrants. See Topic 6.6.)