Effects on Urban Areas

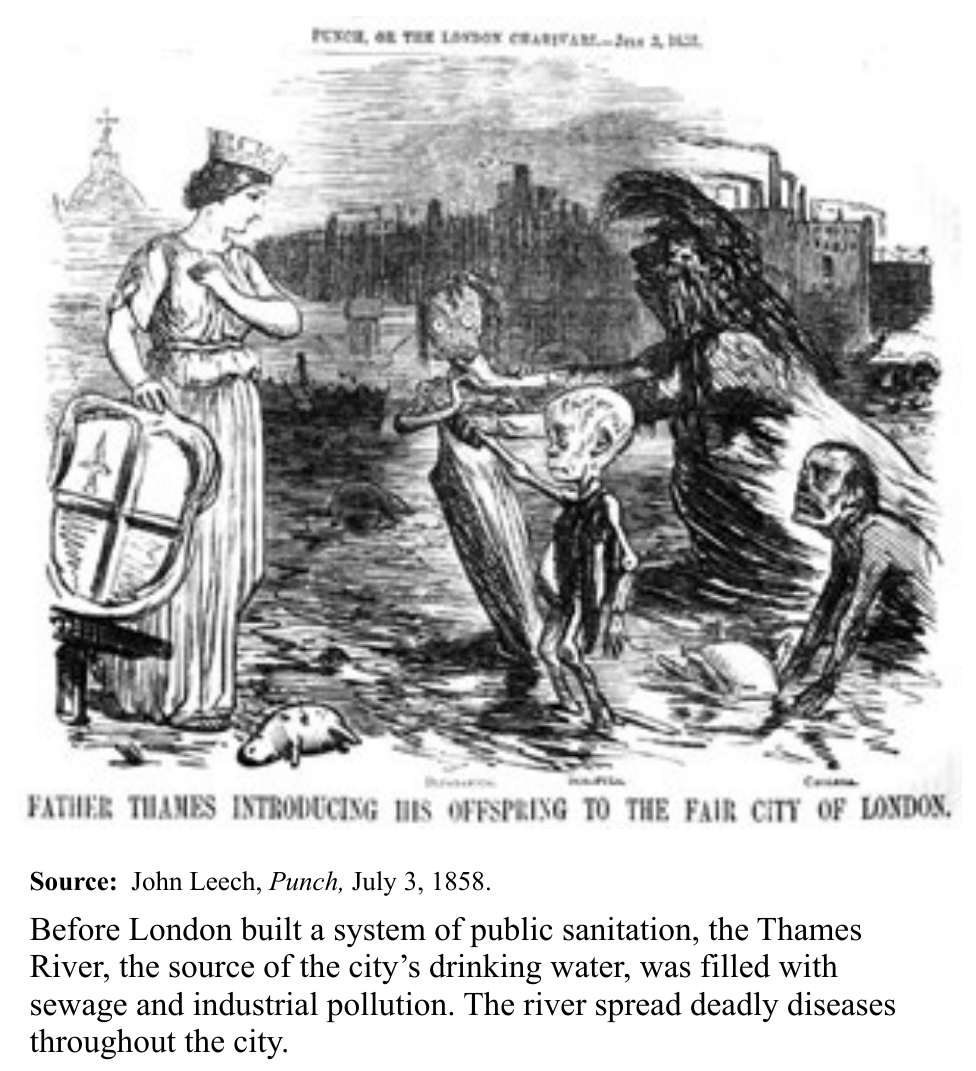

For the first half of the 19th century, urban areas grew rapidly and with little planning by governments. This development left a damaging ecological footprint and created inhumane living conditions for the cities’ poorest residents, members of the working class. Working families crowded into shoddily constructed tenement apartment buildings, often owned by factory owners themselves. Tenements were often located in urban slums (areas of cities where low-income families were forced to live), where industrial by-products such as polluted water supplies and open sewers were common.

In conditions like these, disease, including the much-feared cholera, spread quickly. So did other public health menaces, such as fire and crime and violence. Over time, municipalities created police and fire departments, and several public health acts were passed to implement sanitation reform by creating better drainage and sewage systems, supplying cleaner water, removing rubbish, and building standards to reduce accidents and fire.

Eventually, industrialization led to increased living standards for many. While life could be very hard for poor and working class people, the growing middle class had increased access to goods, housing, culture, and education. The wealth and opportunities of the middle class were among the reasons people continued to stream into cities from rural areas. People living in poverty on farms or in villages hoped to find a better life in an urban center. Many did.

Effects on Class Structure As industrialization spread, new classes of society emerged in Britain. At the bottom rungs of the social hierarchy were those who labored in factories and coal mines. They were known as the working class. Though they helped construct goods rapidly, the technology of interchangeable parts and the factory system’s division of labor had deprived workers of the experience of crafting a complete product. In comparison to the artisans of earlier generations, workers needed fewer skills, so managers viewed them as easily replaceable. Competition for jobs kept wages low. (Connect: Examine the changes in class structure from 17th century Europe to the second industrial revolution. See Topic 4.7.)

While industrialization created low-skilled jobs, it also required those who managed the production of goods to have education and sophisticated skills. A new middle class emerged, consisting of factory and office managers, small business owners, and professionals. They were white-collar workers, those held by office workers. Most were literate and considered middle class.

At the top of the new class hierarchy were the industrialists and owners of large corporations. These so-called captains of industry soon overshadowed the landed aristocracy as the power brokers and leaders of modern society.

Farm Work Versus Factory Work Before industrialization, family members worked in close proximity to one another. Whether women spun fabric in their own homes or landless workers farmed the fields of a landlord, parents and children usually spent their working hours close to each other. Industrialization disrupted this pattern. Industrial machinery was used in large factories, making it impossible to work from home. Thus, individuals had to leave their families and neighborhoods for a long workday in order to earn enough money to survive.

In a factory, work schedules were nothing like they were on a farm or in a cottage industry. The shrill sounds of the factory whistle told workers when they could take a break, which was obviously a culture shock to former- farmers who had previously completed tasks according to their own needs and schedules. Considering that workers commonly spent 14 hours a day, six days a week in a factory, exhaustion was common. Some of these exhausted workers operated dangerous heavy machinery. Injuries and death were common.

Effects on Children The low wages of factory workers forced them to send their children to work also. In the early decades of industrialization, children as young as five worked in textile mills. Because of their small size and nimble fingers, children could climb into equipment to make repairs or into tight spots in mines. However, the dust from the textile machinery damaged their lungs just as much as it did to adults’ lungs.

Children who worked in coal mines faced even more dangerous conditions than those in mills:

• They labored in oppressive heat, carting heavy loads of coal.

• Coal dust was even more unhealthy to breathe than factory dust.

• Mine collapses and floods loomed as constant threats to life.

Effect on Women’s Lives The Industrial Revolution affected women in different ways, depending on their class position. Because their families needed the money, working-class women worked in coal mines (until the practice of hiring women for coal mining was declared illegal in Britain in the 1840s) and were the primary laborers in textile factories. Factory owners preferred to hire women because they could pay them half of what they paid men.

Middle-class women were spared factory work, yet in many ways they lived more limited lives than working-class women. Middle-class men had to leave the house and work at an office to provide for their families. If a wife stayed at home, it was an indication that her husband was capable of being the family’s sole provider. Being a housewife thus became a status symbol.

By the late 1800s, advertising and consumer culture contributed to a “cult of domesticity” that idealized the female homemaker. Advertising encouraged women to buy household products that would supposedly make the home a husband’s place of respite from a harsh modern world. Pamphlets instructed middle-class women on how to care for the home, raise children, and behave in polite society and urged them to be pious, submissive, pure, and domestic. For working-class women the cult of domesticity was even more taxing, as they had to manage the household, care for their children, and work full time.

Industrialization also spurred feminism. When men left a community to take a job, their absence opened up new opportunities for the women who remained home. One political sign of this feminism came in 1848 at Seneca Falls, New York, when 300 people met to call for equality for women.

Effects on the Environment The Industrial Revolution was powered by fossil fuels such as coal, petroleum, and natural gas. Although burning coal produced more energy than burning wood, the effects were extremely harmful. Industrial towns during the late 19th century were choked by toxic air pollution produced by coal-burning factories. Smog (smoke and fog) from factories led to deadly respiratory problems. Water became polluted, also, as the new industries dumped their waste into streams, rivers, and lakes. Cholera, typhoid, and other diseases ravaged neighborhoods.